Pterostylis coccina. Photo by BerndH licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0

Looking as if they have escaped from some sort of modern art exhibit, the flowers of the various greenhood orchids (genus Pterostylis) are as complex as they are beautiful. Native throughout Australia, New Zealand, New Guinea, New Caledonia, and Indonesia, greenhood orchids number around 300 species, all of which are terrestrial. As more attention is paid to their ecology, we are also discovering that many of those 300 species utilize seriously complex trickery to increase their chances of being pollinated.

Pterostylis metcalfei. Photo by Geoff Derrin licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0

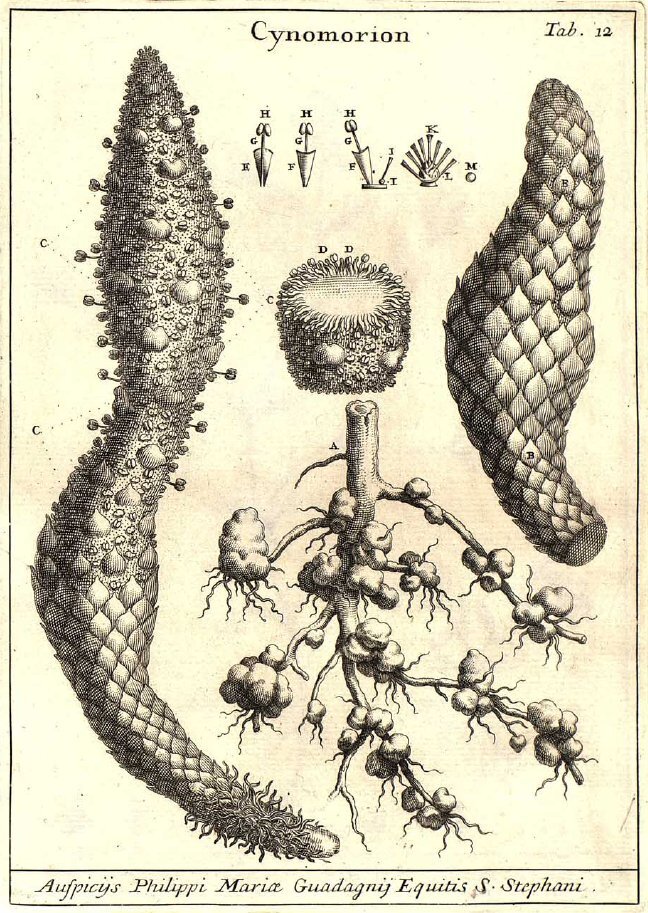

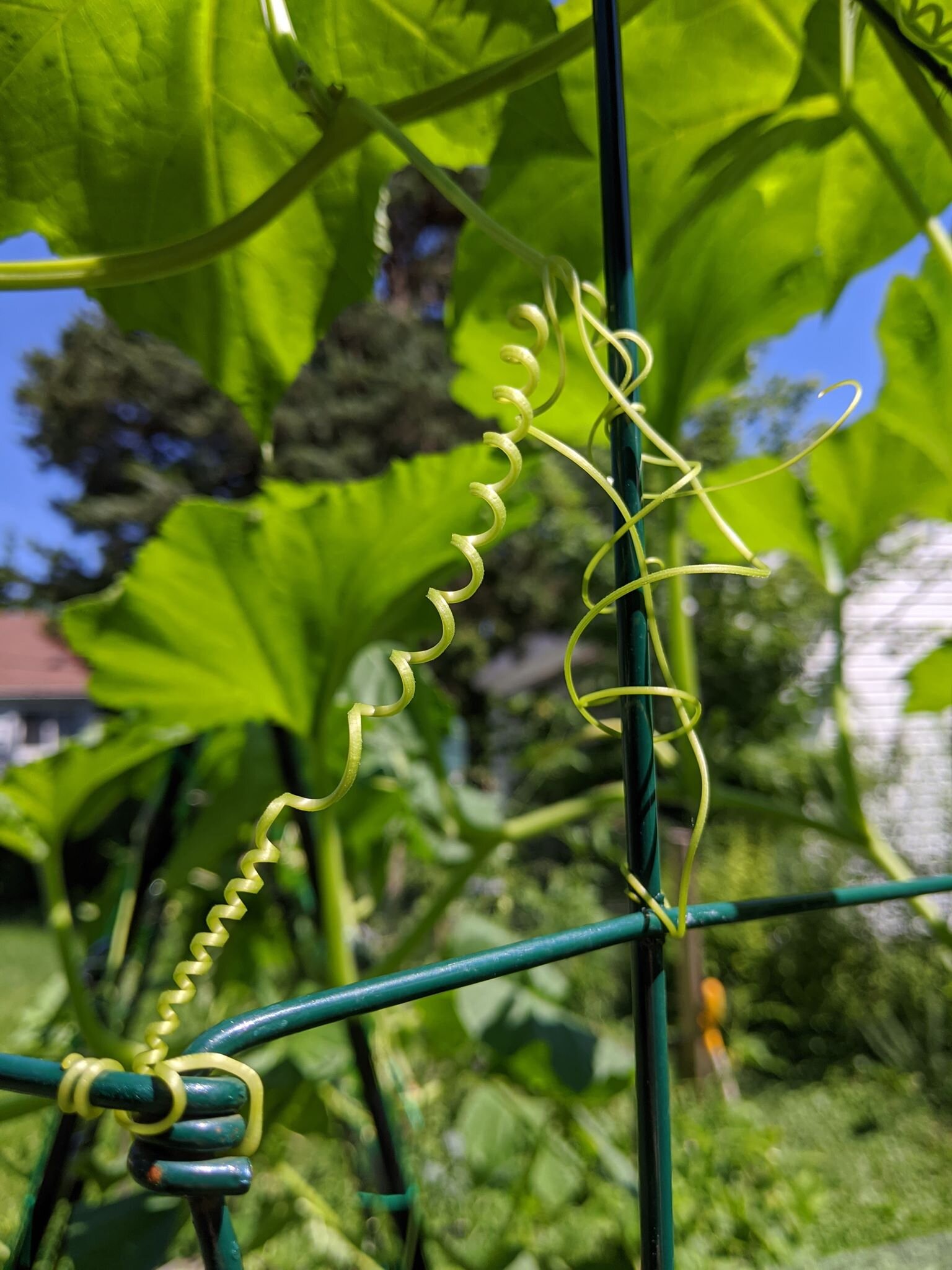

Though they vary in shape, size, and color, the flowers of greenhorn orchids roughly conform to a similar morphological theme. The dorsal sepal and two lateral petals are fused, forming a good-like structure, hence the hooded reference in the common name. On the front of the flower, the two lateral sepals also fuse near their base and taper into two points or wings at the top that give the flowers even more charisma. The whole structure forms a sort-of pitfall trap around the sexual organs. In many species, the lower petal or labellum often sticks up and out of the mouth of the floral tube and is frequently dressed in hairs or other protuberances.

Pterostylis turfosa. Photo by Geoff Derrin licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0

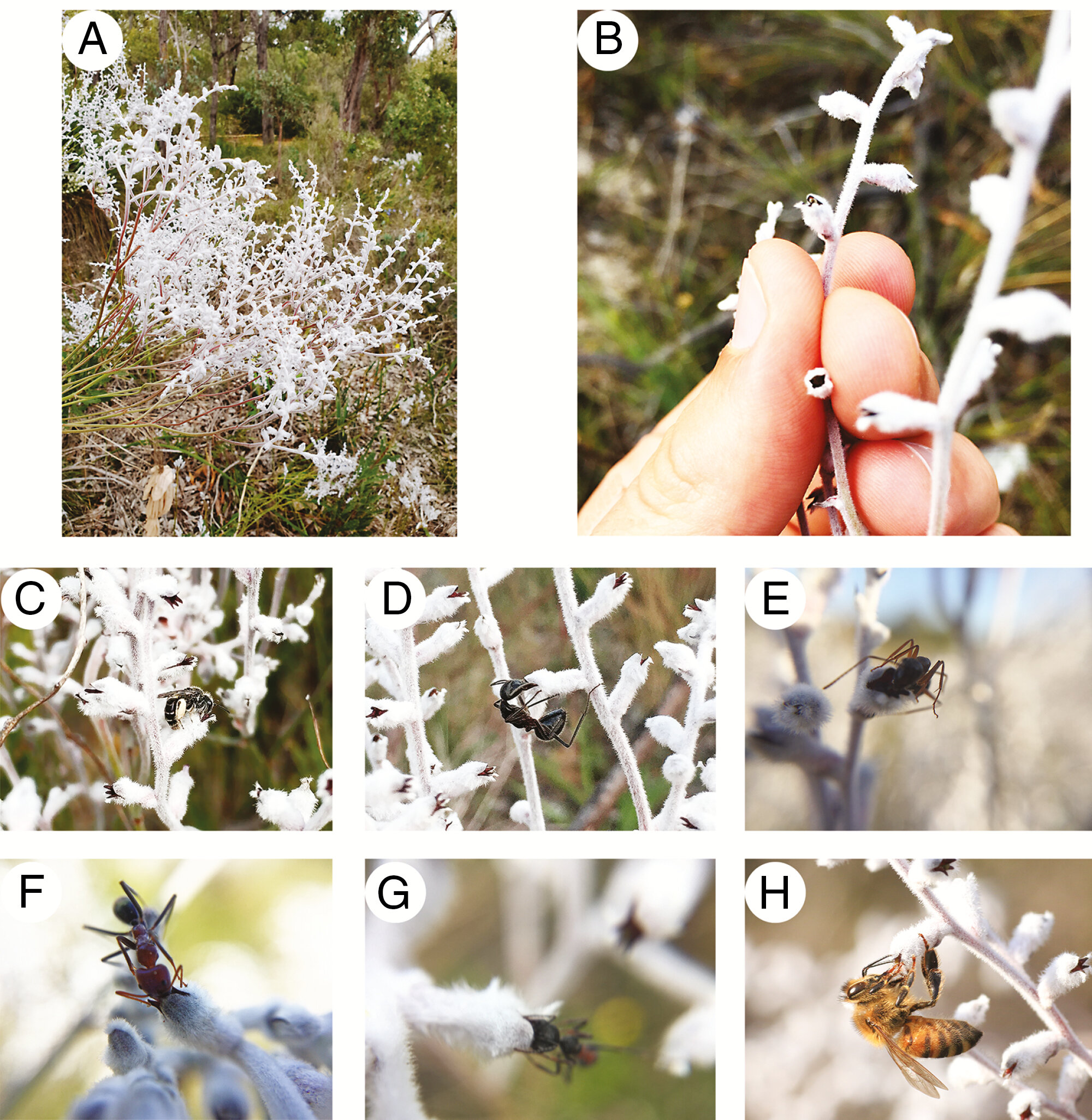

Greenhood orchid flowers are true marvels of evolution. Not only are they structurally complex, they are also painted in various shades of greens, whites, reds, and browns. Of course, all of this intricate beauty serves a single function for these orchids, sex. Essentially, greenhood orchid flowers are pollinator booby traps. Like so many other orchids, the greenhoods are tricksters, luring in their pollinators with the promise of food or even sex but offering nothing in return. Though we still have a lot to learn about pollination in this genus, what evidence we have compiled indicates that the promise of sex is the main ruse the greenhoods employ.

Pterostylis baptistii. Photo by Melburnian licensed under CC BY 3.0

The prevalence of male insects visiting the flowers of many greenhood species tells us these orchids achieve pollination via sexual deception. Lured in by scents that precisely mimic the pheromones of receptive female insects, the males land on the flower and begin searching for a mate. They inevitably begin exploring the labellum, which leads them down into the floral tube. At a certain point in their journey, the male insect will reach a tipping point on the labellum. Like an unbalanced seesaw, the labellum snaps backwards as the insect’s weight shifts, slamming the visitor into the column where it comes into contact with the reproductive organs.

The whole process seems very alarming for the unsuspecting victim. The male insect will struggle quite a bit before it finds a single escape route provided by the floral anatomy that ensures both pollen acquisition and deposition. Experiments have shown that this lever mechanism can be repeated upwards of 3 times within a few hours, so each flower has at least a few attempts to get the process right.

Pterostylis alpina. Photo by Melburnian licensed under CC BY 3.0

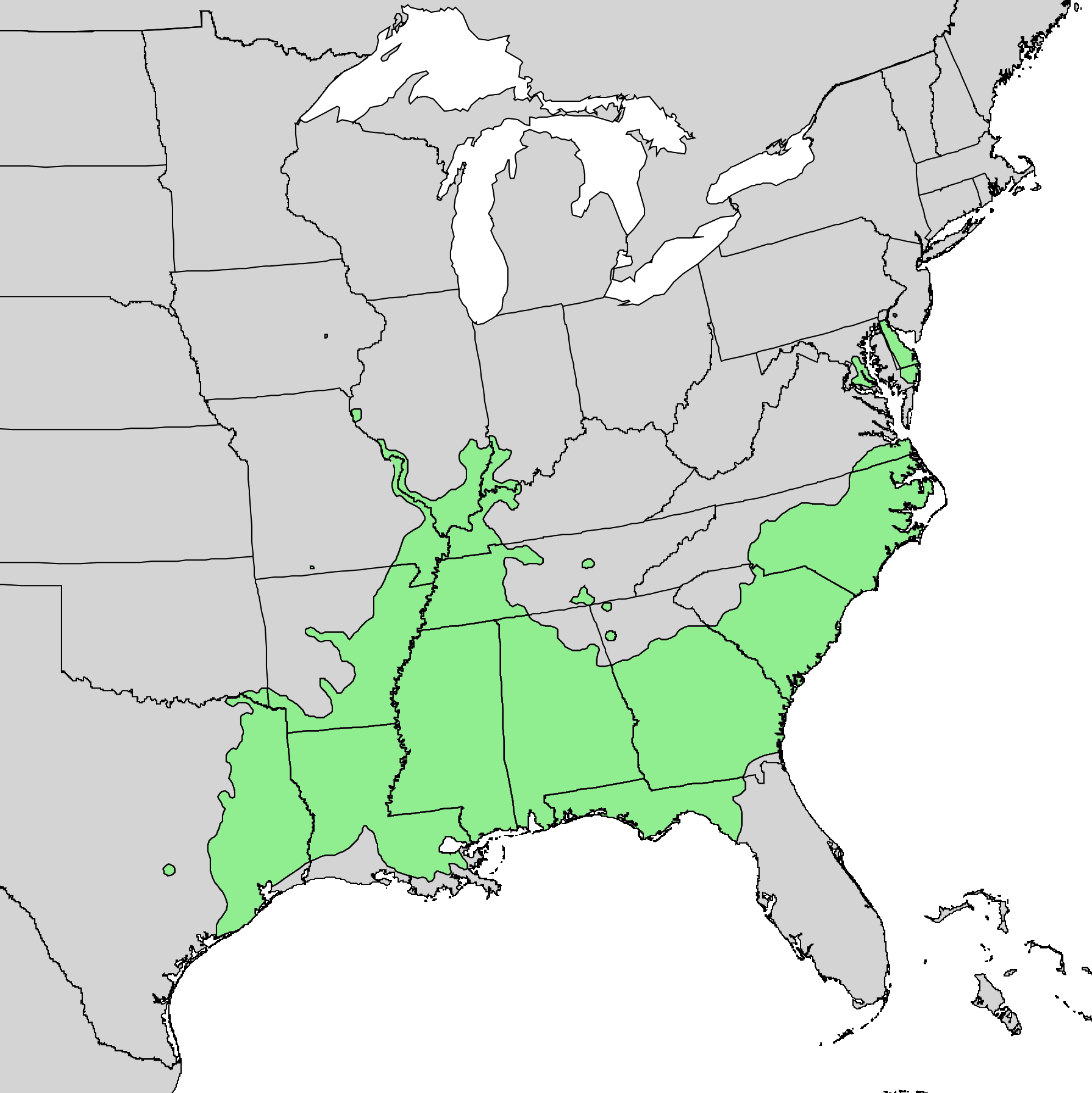

So, who are the insects that fall victim to the greenhood ruse? It turns out that its mostly small flies like fungus gnats and mosquitoes. The few detailed investigations that have been made into the pollination syndromes of these orchids has revealed surprisingly complex and often species-specific relationships between the plants and their pollinators. This makes sense from a chemical standpoint. The mating pheromones of one species of fly or mosquito are unlikely to attract males of different species. As such, the orchids trickery only works on one or possibly even a couple closely related species. Still, many mysteries abound in this diverse and widespread group of orchids and it will take a new generation of curious botanists and ecologists to uncover them.

![(1) Immature stamen surround the style; (2) elongation of the style by which the anthers dehisce and pollen grains are swept on the stylar hairs of the immature style; and (3) further outgrowth of the style, anthers are withered. [SOURCE]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/544591e6e4b0135285aeb5b6/1597935189988-GZOSOLTMYZR2RB20CDOK/spp.JPG)

![Syntrichia caninervis growing in both soil surface and milky quartz. [SOURCE]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/544591e6e4b0135285aeb5b6/1596125329330-RWYPR68OSOIXG5AWE3EN/mossrock.png)

![Tortula inermis (white arrow) and S. caninervis (black arrow) growing in a milky quartz. [SOURCE]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/544591e6e4b0135285aeb5b6/1596128581756-SZLGMLQQ27C9GX0IGMMN/mossrock2.png)

![Tortula inermis was more likely to be found growing under quartz at high elevations. [SOURCE]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/544591e6e4b0135285aeb5b6/1596128741494-5OR9HUY18IL5JK888XY4/t_inermis.jpg)

![(A) Box plot of hypolithic and soil surface S. caninervis shoot length. (B) An S. caninervis shoot fromunder quartz. (C) An S. caninervis shoot from the soil surface. [SOURCE]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/544591e6e4b0135285aeb5b6/1596128644865-RJZXZN3WBZBCXW85B263/journal.pone.0235928.g005.PNG)

![The recently described Cremanthodium wumengshanicum growing at elevation in Yunnan, China. [SOURCE]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/544591e6e4b0135285aeb5b6/1595452902740-1SHVHLYLHXN0VGCR17C4/Cremanthodium_wumengshanicum-novataxa_2015-L._Wang-C._Ren_et_Q.E._Yang.jpg)

![Investigating pollinator visitation among different species of Zaluzianskya. [SOURCE]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/544591e6e4b0135285aeb5b6/1595453007802-011KTFTH4MG6YEFKCL9M/nph13746-fig-0001-m.jpg)

![Waveforms of male signals for nine species in the Enchenopa binotata complex based on host tree identity [SOURCE].](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/544591e6e4b0135285aeb5b6/1594054293879-I5KJI60173XWLJ6OP7HB/Varying_male_signals_that_species_of_Enchenop_binotata_make.png)

![Photo by Nicola Delnevo [SOURCE]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/544591e6e4b0135285aeb5b6/1592594490445-RKITCT8N72D9GVX5TOJP/12349226-4x3-xlarge.jpg)

![(A) Sequential images of a worker penetrating a leaf with its proboscis. (B) A worker cutting into a leaf with its mandibles. (C) Characteristic bee-inflicted damage. [SOURCE]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/544591e6e4b0135285aeb5b6/1590422078311-B6AUBLIBRG2QYEXCJ9EI/F1.large.jpg)

![Star chickweed showing low-growing fertile shoots (front) and taller, sterile shoots (back). [SOURCE]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/544591e6e4b0135285aeb5b6/1589231950907-7YGTJJT7TSVAXG9SYFLO/IMG_0762.JPG)