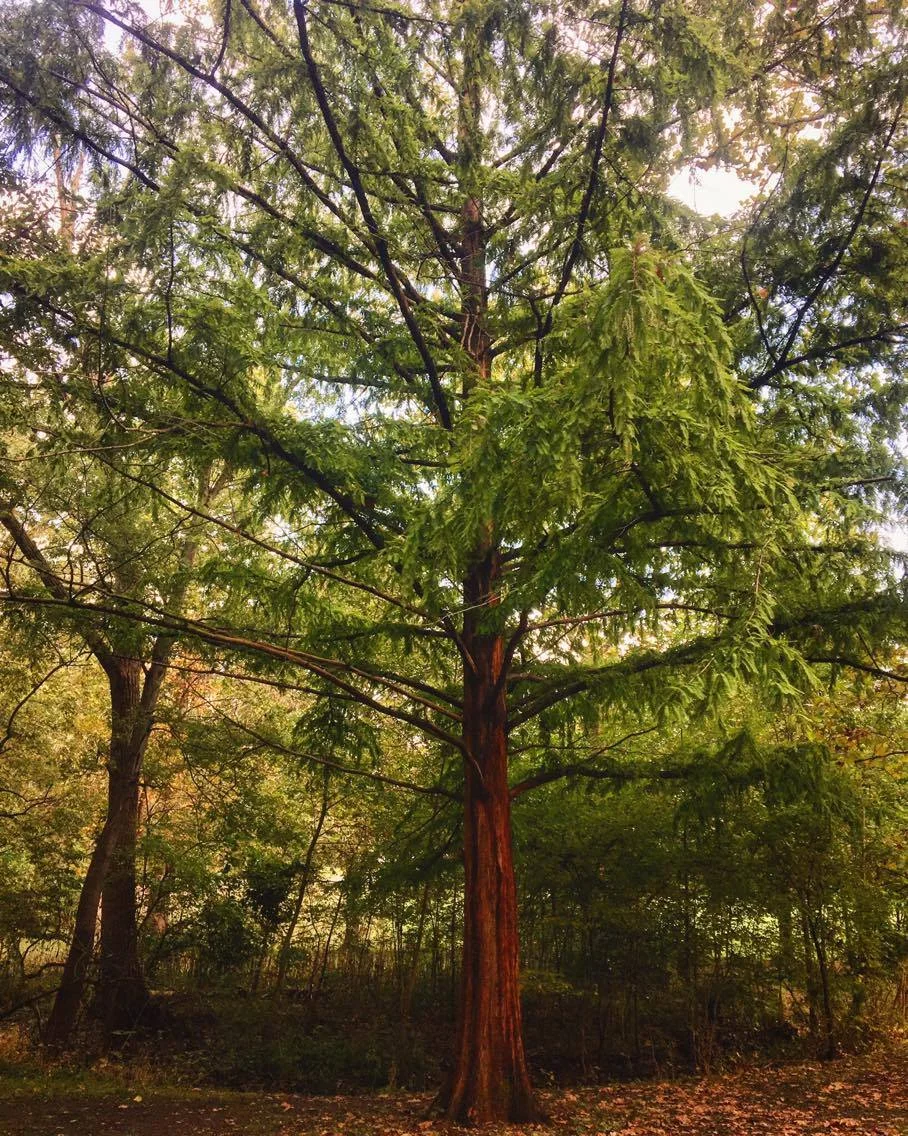

Photo by Ewan Bellamy licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 2.0

Spring time is bulb time. As the winter gives way to warmer, longer days, bulbs are among the first of our beloved botanical neighbors to begin their race for the sun. Functionally speaking, bulbs are storage organs. They are made up of a short stem surrounded by layers of fleshy leaves, which contain plenty of energy to fuel rapid growth. Their ability to maintain dormancy is something most of us will be familiar with.

As you might expect, bulbs are an adaptation for short growing seasons. Their ability to rapidly grow shoots gives them an advantage during short periods of time when favorable growing conditions arrive. Despite the energetic costs associated with supplying and maintaining such a relatively large storage organ, the ability to rapidly deploy leaves when conditions become favorable is very advantageous.

Contrast this with rhizomatous species, which are often associated with a life in the understory (though not exclusively) or in crowded habitats like grasslands where competition for light and space can be fierce. Their ambling subterranean habit allows them to vegetatively "explore" for light and nutrients. What's more, the connected rhizomes allow the parent plant to provide nutrients to the developing clones until they grow large enough to support themselves. Under such conditions, bulbs would be at a disadvantage.

Bulbs have evolved independently throughout the angiosperm tree. Many instances of a switch from rhizomatous to bulbous growth habit occurred during the Miocene (23.03 to 5.332 million years ago) and has been associated with a global decrease in temperature and an increase in seasonality at higher latitudes. The decrease in growing season may have favored the evolution of bulbous plants such as those in the lily family. Today, we take advantage of this hardy habit, making bulbous species some of the most common plants used in gardens.

Further Reading: [1]