Photo by Roberto Fiadone licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0

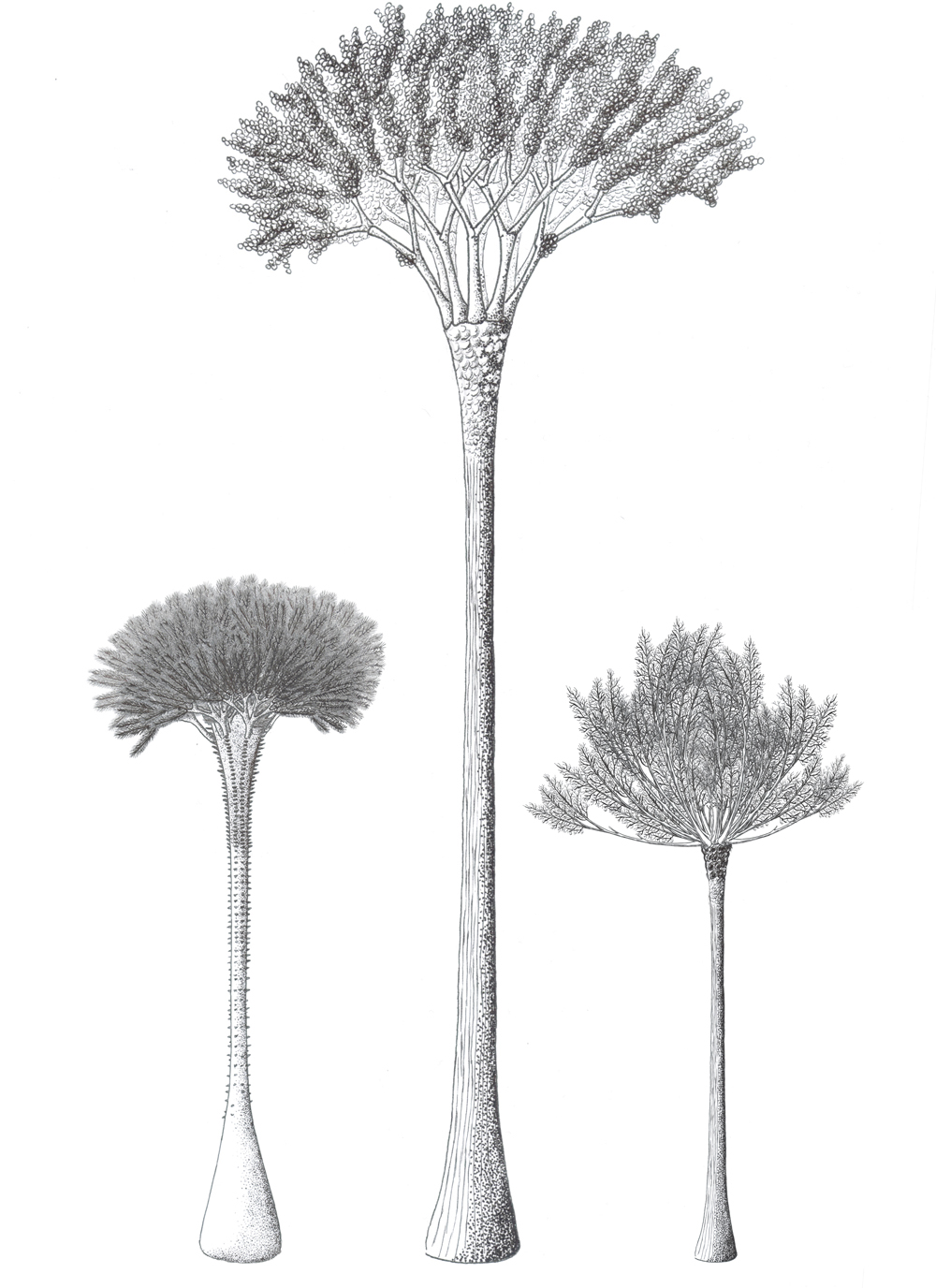

There is more than one way to build a tree. For that reason and more, “tree” is not a taxonomic designation. Arborescence has evolved independently throughout the botanical world and many herbaceous plants have tree-like relatives. I was shocked to learn recently of a plant native to the Pampa region of South America commonly referred to as ombú. At first glance it looks like some sort of fig, with its smooth bark and sinuous, buttressed roots. Deeper investigation revealed that this was not a fig. Ombú is actually an arborescent cousin of pokeweed!

Photo by Dick Culbert licensed under CC BY 2.0

The scientific name of ombú is Phytolacca dioica. As its specific epithet suggests, plants are dioecious meaning individuals are either male or female. Unlike its smaller, herbaceous cousins, ombú is an evergreen perennial. Because they can grow all year, these plants can reach bewildering proportions. Heights upwards of 60 ft. (18 m.) are not unheard of and the crowns of more robust specimens can easily attain diameters of 40 to 50 ft. (12 - 18 m.)! What makes such sizes all the more impressive is the way in which ombú is able to achieve such growth.

Photo by Lanntaron licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0

Ombú is thought to have evolved from an herbaceous ancestor. Cut into the trunk of one of these trees and you will see that this phylogenetic history has left its mark. Ombú do not produce what we think of as wood. Instead, much of the support for branches and stems comes from turgor pressure. Also, the way in which these trees grow is not akin to what you would see from something like an oak or a maple. Whereas woody trees undergo secondary growth in which the cambium layer differentiates into xylem and phloem, thus thickening stems and roots, ombú exhibits a unique form of stem and root thickening called “anomalous secondary thickening.”

Essentially what this means is that instead of a single layer of cambium forming xylem and phloem, ombú cambium exhibits unidirectional thickening of the cambium layer. There are a lot of nitty gritty details to this kind of growth and I must admit I don’t have a firm grasp on the mechanics of it all. The point of the matter is that anomalous secondary thickening does not produce wood as we know it and instead leads to rapid growth of weak and spongy tissues. This is why turgor pressure is so important to the structural integrity of these trees. It has been estimated that the trunk and branches of an ombú is 80% water.

A cross section of an ombú limb showing harder xylem tissues separated by spongy parenchyma that has since disintegrated. Photo by Tony Rodd licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 2.0

Like all members of this genus, ombú is plenty toxic. Despite this, ombú appears to have been embraced and is widely planted as a specimen tree in parks, along sidewalks, and in gardens in South America and elswhere. In fact, it is so widely planted in Africa that some consider it to be a growing invasive issue. All in all I was shocked to learn of this species. It caused me to rethink some of the assumptions I hold onto with some lineages I only know from temperate regions. It is amazing what natural selection has done to this genus and I am excited to explore more arborescent anomalies from largely herbaceous groups.

![[SOURCE]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/544591e6e4b0135285aeb5b6/1509465408526-PS04Q0I13MTWTXHU96XE/image-asset.jpeg)

![A cross section of a Cladoxylopsid trunk showing the hollow center, individual xylem strands, and the network of connective tissues. [SOURCE]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/544591e6e4b0135285aeb5b6/1509465418599-SBMOI12IRYJPVDFDRKZ8/F3.large.jpg)