A post (and photos) by Robbie Q. Telfer

“Every species is a masterpiece, exquisitely adapted to the particular environment in which it has survived.”

-- E.O. mothereffin Wilson

One of the perks of working at The Morton Arboretum is you get to see cool lectures on tree science for free. At one such program, Dr. Mary Ashley from the University of Illinois at Chicago was sharing her research on oak pollen and how far it can travel to fertilize female flowers (far). She looked at not only trees in the Chicago region, but also oaks off the coast of California and in the Chihuahuan Desert of west Texas, as well as throughout Mexico. That latter oak was a shrubby species called Quercus hinckleyi or Hinckley oak. It is able to spread pollen over far distances as well, despite the fact that there are only 123 individuals known to be left. IUCN lists it as Critically Endangered.

As she was telling us this, it occured to me that I would be in West Texas soon to visit my sister-in-law, so afterwards I approached Dr. Ashley and asked if there was any way I could have the coordinates of Q. hinckleyi so that I could visit it, take a selfie, and luxuriate in the presence of something so rare. I made it clear to her that I understood just how important it was to keep this information a secret, because the last thing this relict needs is to be uprooted by poachers. Which I wish wasn’t a concern, but it is.

Dr. Ashley put me in touch with her colleague Janet Backs who graciously shared the coordinates. I could see the plants from Google maps satellite view. There they were. I probably waved at the computer screen sheepishly.

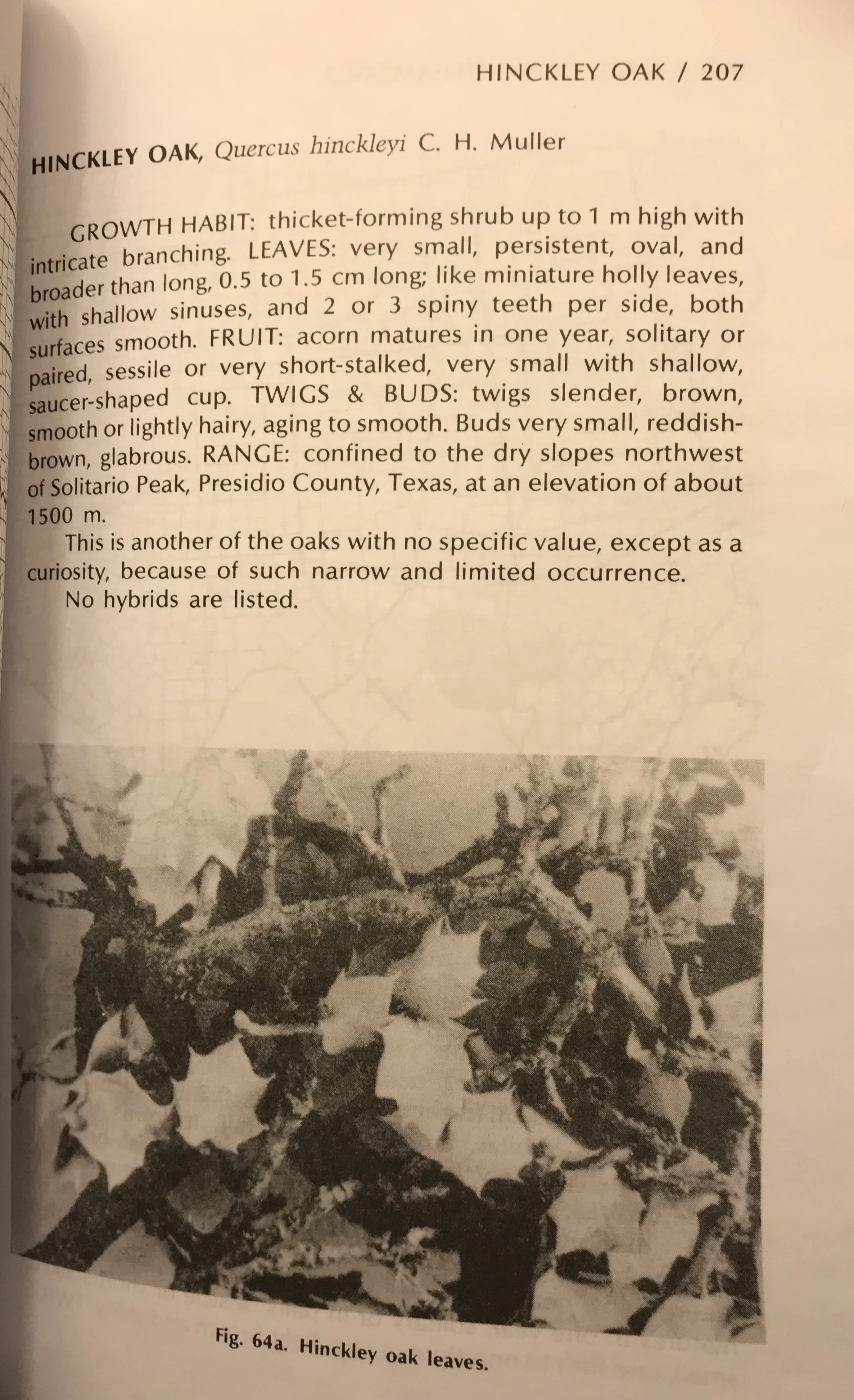

As I waited for my time to bask in the majesty of botanical greatness, I consulted my copy of Oaks of North America (1985) by Howard Miller and Samuel Lamb to see what the entry for hinckleyi said.

Notably, it mentions that “This is another of the oaks with no specific value, except as a curiosity.” More on that later.

After much anticipation, the time was upon us. I decided to drive out to the plants in my rental first thing in the morning after getting to Texas. The Chihuahuan Desert is an astounding place that my Illinoisan eyes weren’t altogether prepared for. It is perhaps the most biodiverse desert in the world, and compared to our prairies, woodlands, and wetlands, it feels like a different planet. Some of the cooler plants I got to see were tree cholla (Cholla sp.), Havard’s century plant (Agave havardiana), Wright’s cliffbrake (Pellaea wrightiana), and little buckthorn (Condalia ericoides). And also a family of introduced aoudads with TWO adorable babies. I also got to see my first javelina (as roadkill) and all kinds of birds new to me.

Tree cholla (Cholla sp.)

Havard’s century plant (Agave havardiana)

Wright’s cliffbrake (Pellaea wrightiana)

Little buckthorn (Condalia ericoides)

Aoudads in the distance.

Finally I got to the coordinates - luckily google preloaded the directions on my phone because there was absolutely no cell service where I was. I parked and walked to the plants. And lo, I present to you, Quercus hinckleyi.

It’s in the white oak family, which I guess means more than just “has round leaves.” These leaves look like holly, and even the shed ones on the ground still had some stabbiness left in them. It’s quite diminutive - certainly compared to any oak I’ve ever seen and even by shrub standards. I’d pinch its cheeks if that wouldn’t make my fingers bleed. After getting the pics I needed and doing the atheist’s version of saying a prayer over it, I floated back to my car like a cartoon cat in love.

The rest of the trip was great and I can’t wait to go back.

Since returning, I have shown several of my non-plant nerd friends the pics of hinckleyi and they seem politely impressed but not, like, actually impressed. This is totally understandable! If your experience with plants is on the order of what looks best in a planting or what tastes best in your tummy, this shrub is not for you. After all “it’s only value is as a curiosity.”

I don’t know about that. I feel like it’s value is greater than that for humans - it’s a window into the North American continent before the climate shifted 10,000 years ago, it’s an individual member of our vast botanical heritage, it is unique, it is adorbs, and it helped Dr. Ashley, and therefore us, understand more things about the movement of oak pollen.

But beyond what it does for US, what if, and hear me out, what if it has a right to existence on its own, without being displaced by pipelines or aoudads or poachers? It is a member of its ecological community, and just like I feel a loss when a member of my community passes, we don’t have the language to articulate what is felt when a member of an ecosystem winks out forever.

Janet Backs told me that she heard of someone who was trying to poach acorns from a subpopulation of hinckleyi and that the landowners where that shrub is actually chased those folks for miles and miles down the road. I love that. I wish every single threatened species/subpopulation had someone who understood its value beyond what it does for humans enough to chase people, possibly with a gun, for miles and miles.

I have had a paltry bucket list for most of my adult life - boring stuff like meeting my heroes or getting to a 7th bowl of never-ending-pasta. But despite their apparent lack of reverence for Q. hinckleyi I think a pretty good guiding list for me would be to visit each of the 77 oaks of North America in their native habitats. I know they won’t all be as special as this experience, but what better way to visit the corners of this continent and its myriad ecological communities, than by visiting each of its oaks? I currently can’t think of any, and would invite anyone to, if not fund me, join me.