Photo by Christian Fischer licensed by CC BY-SA 3.0

For plants, the transition from water to land was a monumental achievement that changed our world forever. Such a transition was fraught with unique challenges, not the least of which being the ever present threat of desiccation. A new study now suggests that those early land plants already had the the tools to deal with drought and they have their aquatic algal ancestors to thank.

One of the keys to being able to survive drought is being able to detect it in the first place. Without some sort of signalling pathway, plants would not be able to close up stomata and channel vital water and nutrients to more important tissues and organs. As such, elucidating the origins and function of drought signalling pathways in plants has been of great interest to science.

One key set of pathways involved in plant drought response is collectively referred to as the “chloroplast retrograde signaling network.” I’m not even going to pretend that I understand how these pathways operate in any detail but there is one aspect of this network that is the key to this recent discovery. It involves the means by which drought and high-light conditions are sensed in one part of the plant and how that information is then communicated to the rest of the plant. When this signalling pathway is activated, the plant can then begin to produce enzymes that go on to activate defense strategies such as stomatal closure.

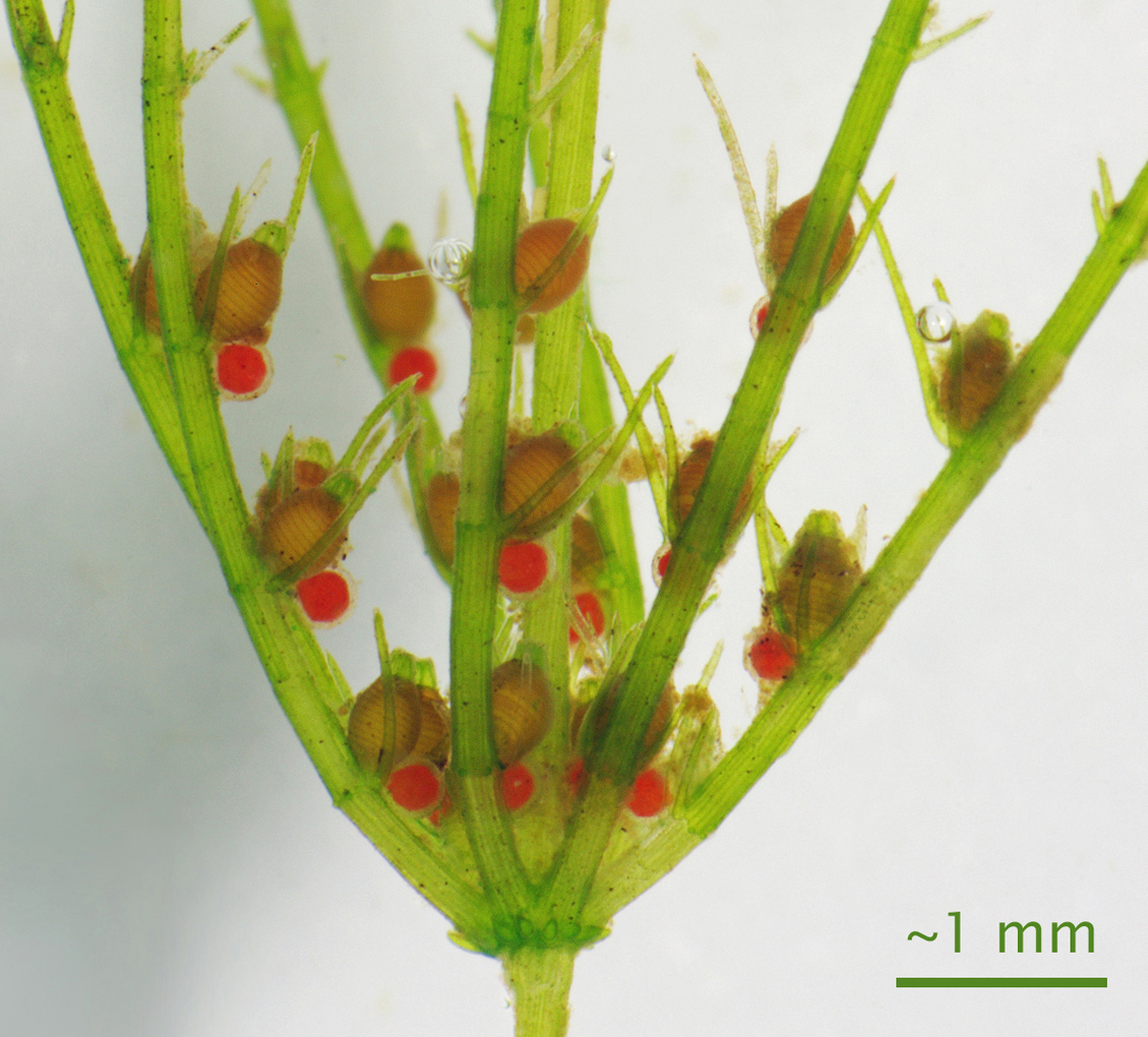

Chara braunii - a modern day example of a streptophyte alga. Photo by Show_ryu licensed under the GNU Free Documentation License

The surprise came when researchers at the Australian National University, in collaboration with researchers at the University of Florida, decided to study the chloroplast retrograde signaling network in more detail. They were interested in the inner workings of this process in relation to stomata. Stomata are tiny pores on the leaves and stems of terrestrial plants that regulate the exchange of gases like CO2 and oxygen as well as water vapor. To add some controls to their experiment, the team added a few species of aquatic algae into the mix. Algae do not produce stomata and therefore they reasoned that no traces of chloroplast retrograde signaling network enzymes should be present.

This is not what happened. Instead, the team discovered that the enzymes in question also showed up in a group of algae known as the streptophytes. This was exciting because streptophyte algae hail from the lineage thought to be ancestral to all land plants. It appears that the tools necessary for terrestrial plants to survive drought were already in place before their ancestors ever left the water.

Why this is the case could have something to do with the streptophyte lifestyle. Today, these algae are known to tolerate very tough conditions. Though outright drought is rarely a threat for these aquatic algae, they nonetheless have to deal with scenarios that resemble drought such as high salinity. Streptophyte algae found growing in ephemeral pools must cope with ever increasing concentrations of salinity as the water around them evaporates. It is possible that this drought signalling pathway may have evolved as a response to hyper-saline conditions such as these. Regardless of what was going on during those early days of plant evolution, this research indicates that the ability for terrestrial plants to deal with drought evolved before their ancestors ever left the water.

The closer we look, the more we can appreciate that evolution of important traits isn’t always de novo. More often it appears that new innovations result from a retooling of of older genetic equipment. In the case of land plants, a signalling pathway that allowed their aquatic ancestors to deal with water loss was coopted later on by organs such as leaves and stems to deal with the stresses of life on land. As the old saying goes, “life uhhh… finds a way.”