Photo by Tim Waters licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 2.0

Back in 1980, a school teacher on the island of Rodrigues sent his students out to look for plants. One of the students brought back a cutting of a shrub that astounded the botanical community. Ramosmania rodriguesii, more commonly known as café marron, was up until that point only known from one botanical description dating back to the 1800's. The shrub, which is a member of the coffee family, was thought to have been extinct due to pressures brought about during the colonization of the island (goats, invasive species, etc.). What the boy brought back was indeed a specimen of café marron but the individual he found turned out to be the only remaining plant on the island.

News of the plant quickly spread. It started to attract a lot of attention, not all of which was good. There is a belief among the locals that the plant is an herbal remedy for hangovers and venereal disease (hence its common name translates to ‘brown coffee’) and because of that, poaching was rampant. Branches and leaves were being hauled off at a rate that was sure to kill this single individual. It was so bad that multiple layers of fencing had to be erected to keep people away. It was clear that more was needed to save this shrub from certain extinction.

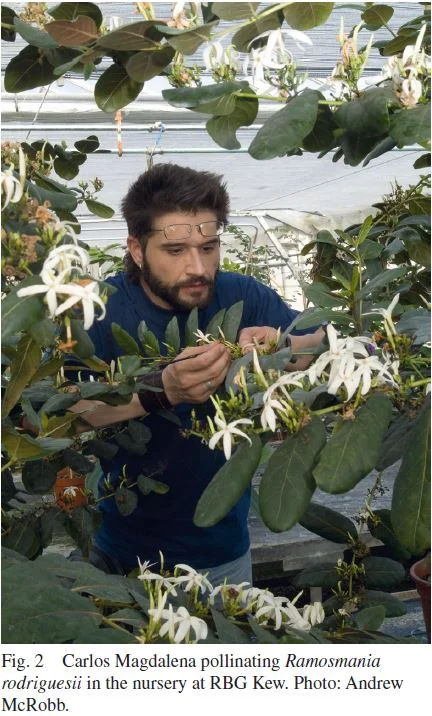

Cuttings were taken and sent to Kew. After some trial and tribulation, a few of the cuttings successfully rooted. The clones grew and flourished. They even flowered on a regular basis. For a moment it looked like this plant had a chance. Unfortunately, café marron did not seem to want to self-pollinate. It was looking like this species was going to remain a so-called “living dead” representative of a species no longer able to live in the wild. That is until Carlos Magdalena (the man who saved the rarest water lily from extinction) got his hands on the plants.

The key to saving café marron was to somehow bypass its anti-selfing mechanism. Because so little was known about its biology, there was a lot of mystery surrounding its breeding mechanism. Though plenty of flowers were produced, it would appear that the only thing working on the plant were its anthers. They could get viable pollen but none of the stigmas appeared to be receptive. Could it be that the last remaining individual (and all of its subsequent clones) were males?

This is where a little creativity and a lot of experience paid off. During some experiments with the flowers, it was discovered that by amputating the top of the stigma and placing pollen directly onto the wound one could coax fertilization ans fruiting. From that initial fruit, seven seeds were produced. These seeds were quickly sent to the propagation lab but unfortunately the seedlings were never able to establish. Still, this was the first indication that there was some hope left for the café marron.

After subsequent attempts at the stigma amputation method ended in failure, it was decided that perhaps something about the growing conditions of the first plant were the missing piece of this puzzle. Indeed, by repeating the same conditions the first individual was exposed to, Carlos and his team were able to coax some changes out of the flowering efforts of some clones. Plants growing in warmer conditions started to produce flowers of a slightly different morphology towards the end of the blooming cycle. After nearly 300 attempts at pollinating these flowers, a handful of fruits were formed!

From these fruits, over 100 viable seeds were produced. What’s more, these seeds germinated and the seedlings successfully established. Even more exciting, the seedlings were a healthy mix of both male and female plants. Carlos and his team learned a lot about the biology of this species in the process. Thanks to their dedicated work, we now know that café marron is protandrous meaning its male flowers are produced before female flowers.

However, the story doesn’t end here. Something surprising happened as the seedlings continued to grow. The resulting offspring looked nothing like the adult plant. Whereas the adult plant has round, green leaves, the juveniles were brownish and lance shaped. This was quite a puzzle but not entirely surprising because the immature stage of this shrub was not known to science. Amazingly, as the plants matured they eventually morphed into the adult form. It would appear that there is more to the mystery of this species than botanists ever realized. The question remained, why go through such drastically different life stages?

The answer has to do with café marron's natural predator, a species of giant tortoise. The tortoises are attracted to the bright green leaves of the adult plant. By growing dull, brown, skinny leaves while it is still at convenient grazing height, the plant makes itself almost invisible to the tortoise. It is not until the plant is out of the range of this armoured herbivore that it morphs into its adult form. Essentially the young plants camouflage themselves from the most prominent herbivore on the island.

Thanks to the efforts of Carlos and his team at Kew, over 1000 seeds have been produced and half of those seeds were sent back to Rodrigues to be used in restoration efforts. As of 2010, 300 of those seed have been germinated, opening up many more opportunities for reintroduction into the wild. Those early trials will set the stage for more restoration efforts in the future. It is rare that we see such an amazing success story when it comes to such an endangered species. We must celebrate these efforts because they remind us to keep trying even if all hope seems to be lost. My hat is off to Carlos and the dedicated team of plant conservationists and growers at Kew.