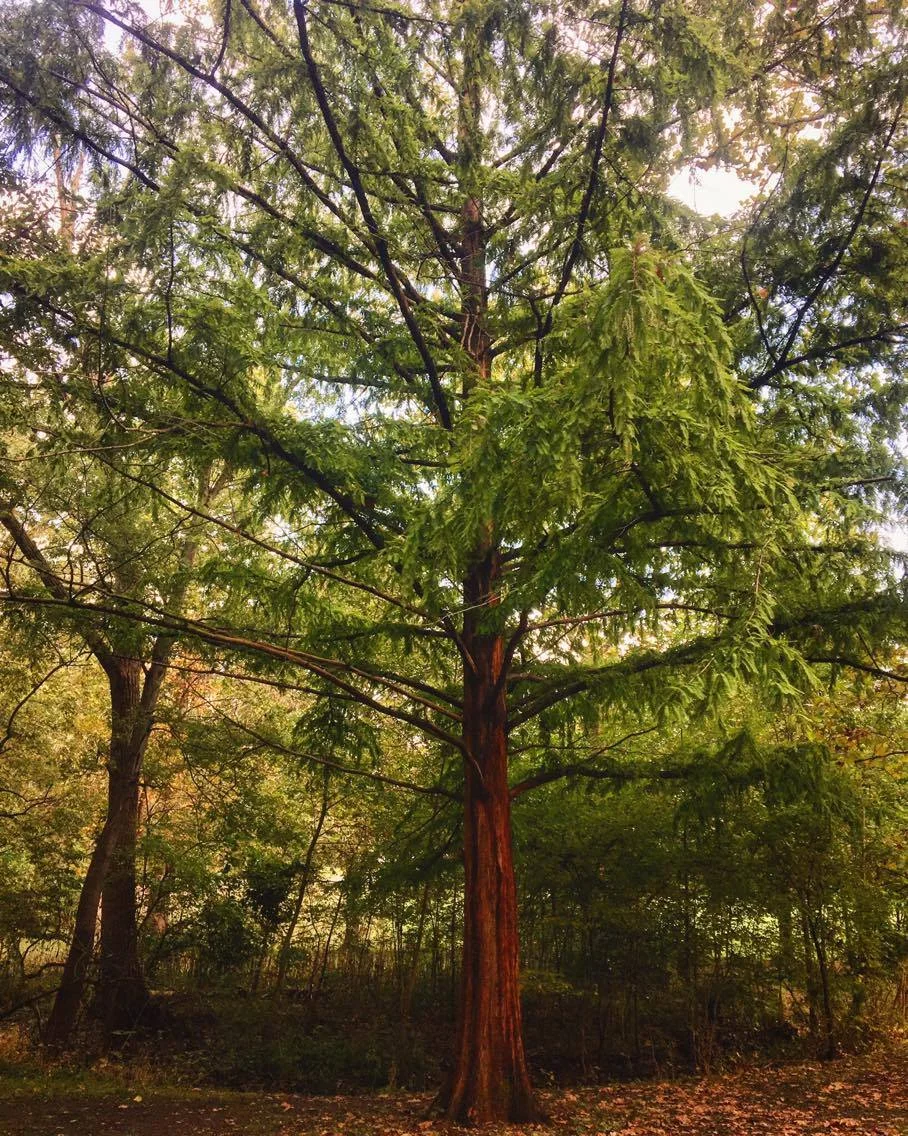

The dawn redwood (Metasequoia glyptostroboides) is one of the first trees that I learned to identify as a young child. My grandfather had one growing in his backyard. I always thought it was a strange looking tree but its low slung branches made for some great climbing. I was really into paleontology back then so when he told me this tree was a "living fossil" I loved it even more. It would be many years before I would learn the story behind this interesting conifer.

Photo by Ruth Hartnup licensed under CC BY 2.0

Along with the coast redwood (Sequoia sempervirens) and giant sequoia (Sequoiadendron giganteum), the dawn redwood makes up the subfamily Sequoioideae. Compared to its cousins, the dawn redwood is the runt, however, with a max height of around 200 feet (60 meters), a mature dawn redwood is still an impressive sight.

Until 1944 the genus Metasequoia was only known from fossil evidence. As with the other redwood species, the dawn redwood once realized quite a wide distribution. It could be found throughout the northern regions of Asia and North America. In fact, the fossilized remains of these trees make up a significant proportion of the fossils found in the Badlands of North Dakota.

Fossil evidence dates from the late Cretaceous into the Miocene. The genus hit its widest distribution during a time when most of the world was warm and tropical. Evidence would suggest that the dawn redwood and its relatives were already deciduous by this time. Why would a tree living in tropical climates drop its leaves? Sun.

Regardless of climate, axial tilt nonetheless made it so that the northern hemisphere did not see much sun during the winter months. It is hypothesized that the genus Metasequoia evolved its deciduous nature to cope with the darkness. Despite its success, fossil evidence of this genus disappears after the Miocene. For this reason, Metasequoia was thought to be an extinct lineage.

Photo by Georgialh licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0

All of this changed in 1943 when a Chinese forestry official collected samples from a strange tree growing in Moudao, Hubei. Though the samples were quite peculiar, World War II restricted further investigations. In 1946, two professors looked over the samples and determined them to be quite unique indeed. They realized that these were from a living member of the genus Metasequoia.

Thanks to a collecting trip in 1948, seeds of this species were distributed to arboretums around the world. The dawn redwood would become quite the sensation. Everyone wanted to own this living fossil. Today we now know of a few more populations. However, most of these are quite small, consisting of around 30 trees. The largest population of this species can be found growing in Xiaohe Valley and consists of around 5,000 individuals. Despite its success as a landscape tree, the dawn redwood is still considered endangered in the wild. Demand for seeds has led to very little recruitment in the remaining populations.