Species of the genus Nepenthes are as bizarre as they are beautiful. Known the world around for their carnivorous lifestyle, these plants looks like something out of a macabre art exhibit. It is easy to get caught up in this beauty. I often find myself lost in thought while staring at full grown specimen. How did this genus come to be? Why are they so diverse? What is going on with the morphology of these plants?

Nepenthes hail from nutrient poor habitats, which has driven them to supplement their growth with nutrients gained via the breakdown of a variety of organisms. The business ends of a Nepenthes are their pitchers. We get so caught up in the bewildering diversity of shapes, colors, and sizes that we often overlook them as the anatomical marvels of evolution that they truly are. Whereas the main body of these plants often look quite similar among different species, it's the pitchers that really allow us to separate them out as distinct species. Pitcher morphology not only gives us a convenient means to identify these plants, research is now showing that the structure of these pitchers is likely to be the driving force in their evolution.

Let's back up for a second. Before we get to the subject of adaptive radiation, we should take a closer look at the anatomy of these plants. To put it simply, the pitchers of Nepenthes are actually leaves, albeit highly modified versions. What we readily recognize as the photosynthetic leaves of a Nepenthes plant are actually modified leaf bases or petioles. Over evolutionary time, these bases have flattened to increase the amount of surface area available for photosynthesis.

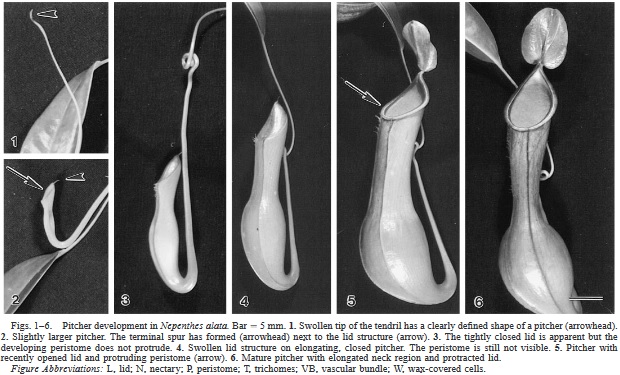

From the tip of each of these "leaves" is produced a tendril. Gradually this tendril will elongate and the tip starts to swell. This tip will eventually become the pitcher. The pitchers themselves are highly modified leaves. They are some of the most specialized leaves in all of the plant kingdom. As the tip grows larger, it becomes clear that there is a distinctive lid apparatus. Once the pitcher is fully mature, this lid pops open revealing the death trap filled with digestive fluids.

As if producing pitchers wasn't cool enough, each species of Nepenthes produces two distinct forms - lower pitchers, which are produced by young plants as well as on mature plants near the ground, and upper pitchers, which are produced up on the climbing stems as they vine through the canopy. The upper and lower pitchers look radically different from one another to the point that one may easily confuse them for different species. The reason for such stark differences has to do with the type of prey captured. Lower pitchers are generally larger and can capture prey that crawls along the forest floor. Upper pitchers tend to be more slender and most often capture flying insects as well as other creepy crawlies hanging out in the forest canopy.

The key to the success of these traps seems pretty straight forward - insects attracted by bright colors and sweet nectar land on the traps and fall to their death. Certainly this holds true throughout the genus, however, there are at least two major variations on this theme and a handful of bizarre mishmashes. As the lid of a Nepenthes pitcher starts to open, a ring of tissue called the peristome unfurls. The shape and color varies wildly between species and this has to do with the methods in which they capture their prey. These variations are the key to the amazing diversity of Nepenthes we see throughout the range of this genus.

Nepenthes vogelii

The first of the three strategies is referred to as the 'insect aquaplaning' strategy. Insects walking around on the peristome of the pitcher find it hard to get a foothold. These are species such as N. raja, N. ampullaria, and N. bicalcarata (just to name a few). The slipperiness of the peristome of these species is further enhanced when humidity is high. Considering how much it rains in these habitats, it is no wonder why capture efficiency is often as high as 80%. Although there is some variation on this theme, pitchers that utilize the insect aquaplaning strategy often lack waxy cells on the interior of the pitcher walls.

Slippery pitcher walls are the second strategy that Nepenthes have converged upon. These are species such as N. diatas, N. mirabilis, and N. alata (again, just to name a few) Insects attracted to the pitchers are often lured in by sweet nectar. Once they cross the lip of the pitcher, prey find it hard to hang on and inevitably fall inside. Once this happens, waxy cells lining the interior walls make it impossible for anything to climb back out. It should be mentioned that a slippery peristome and waxy pitcher walls are not mutually exclusive. That being said, there are clear trends among species that show a reduction in waxy cells as peristome size and slope increases.

This brings us to the oddballs. There are species like N. lowii, whose pitchers function as a toilet bowl for shrews, and N. aristolochioides, whose pitchers seemed to have abandonded both strategies and now function as light traps similar to what we see in Darlingtonia. Regardless of their strategy, the diversity in trapping mechanisms appear to be the driving force behind the bewildering diversity of Nepenthes.

Nepenthes aristolochioides

All of the evidence taken together shows that prey capture is at the core of this radiation. There seems to be incredibly strong selective pressures that result in strong divergence in pitcher morphology. The disruptive selection that seems to be driving a wedge between the insect aquaplaning strategy and the waxy wall strategy may have its roots in reducing competition. Nutrients are low and competition for food is high. Different Nepenthes species could be evolving to capture different kinds of prey. Even closely related species such as N. ampullaria, N. rafflesiana, N. mirabilis, N. albomarginata, and N. gracilis all seem to occupy their own unique spot on the spectrum of prey capture strategy.

It could also be that Nepenthes are responding to the specific characteristics of the habitats in which they are found. Those inhabiting drier sites may favor the waxy wall strategy whereas those living in wetter habitats tend to favor the slippery peristome. More work needs to be done to investigate where and how these different strategies are maximized. Until then, I think it is safe to say that the diversity of this incredible genus has a lot to do with obtaining food.

Photo Credits: [1]

Further Reading: