Discussions about pitcher plants usually revolve around the fact that they trap and eat insects and other animals. However, there are a handful of organisms out there that turn the table on pitcher plants, reminding us that these botanical carnivores can become food themselves. Spend any amount of time surveying pitcher plant populations in southeastern North America and you are likely to encounter at least one such species of pitcher plant eater.

There are three species of pitcher plant moths in the genus Exyra and all of them would not exist if it were not for pitcher plants in the genus Sarracenia. Whereas E. ridingsii and E. semicrocea are largely restricted to southeastern portions of North America, E. fax can be found as far north as Newfoundland. These three species also vary in their dietary specificity. As you can probably ascertain from its distribution, E. fax is a purple pitcher plant (S. purpurea) but will also feed on the southern pitcher plant (S. rosea) in the southern portions of its range. Exyra ridingsii is also a dietary specialist, feeding only on the pitchers of the yellow pitcher plant (Sarracenia flava). Alternatively, E. semicrocea is a generalist and can be found feeding on a variety of Sarracenia species.

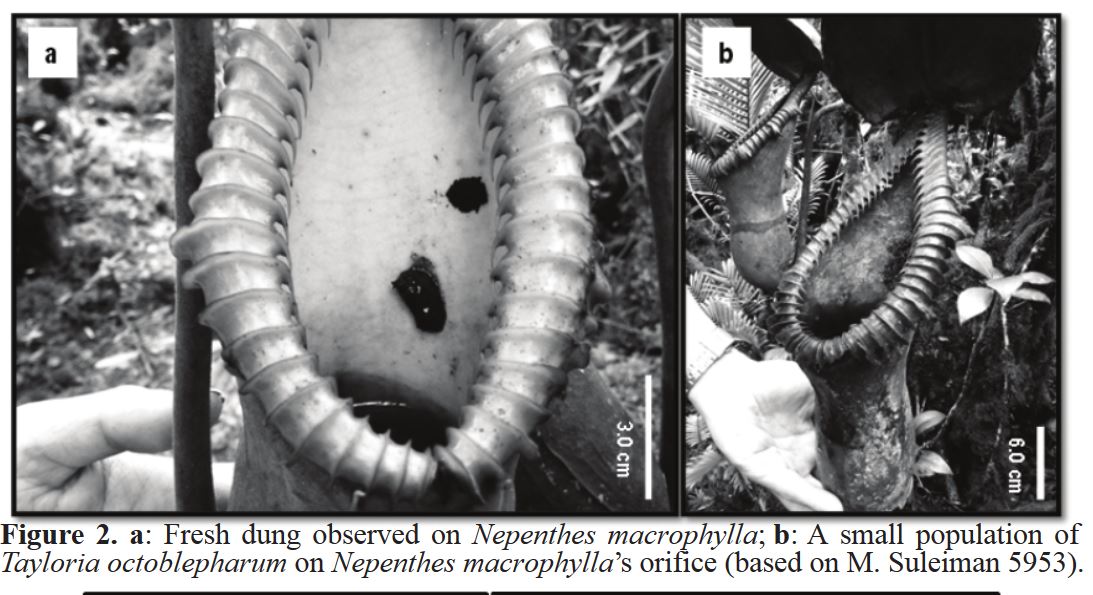

An Exyra caterpillar busy feeding on a Sarracenia flava pitcher.

Both caterpillars and adult moths are physically adapted to living within the slippery interior of the pitcher walls. Microscopic analyses of their feet have revealed specialized morphological adaptations that allow them to cling to the waxy walls of the pitcher. The caterpillars may also benefit from their ability to spin silken lines. Interestingly, the moths are only ever found perched upright in the pitchers. Even when they mate (which also occurs within the pitcher), they do so at a 90 degree angle so that neither partner is facing downward. It is thought that they must remain mostly upright in order for their feet to properly cling to the waxy wall.

Regardless of which pitcher plant they are eating, these three moths all behave similarly throughout their lifecycle. The caterpillars are hatched within a pitcher. Immediately they begin feeding on the wall of the pitcher. They will only eat the interior cells of the pitcher wall, leaving a thin layer of tissue on the outside wall. This makes the pitcher look as if it is covered in translucent, brown windows. At some point in their development, the caterpillars will also spin a layer of silk over the mouth of the pitcher. This protects them from predators like lynx spiders and cuts off the pitchers ability to capture prey (more on this in a bit).

As the caterpillars grow, they will occasionally move to new pitchers. At larger sizes, their feeding damage can be quite extensive, damaging the walls of the pitcher to the point that it loses its structural integrity and folds over. This can also serve to protect the caterpillar from predators while similarly reducing the ability of the plant to capture food. After their fifth larval instar, the caterpillars will move to a new, usually undamaged pitcher. In many instances, they will crawl to the bottom and chew a small hole in the side, draining the pitcher of its digestive fluids. They will then pupate just above the drainage hole.

Signs of Exyra feeding damage.

After a period of time that varies between species, adult moths will emerge. The adults are adorable little critters dressed in shades of yellow and black. They are also very secretive and do not leave the pitchers until nightfall. Even then, they only do so to mate and lay eggs in new pitchers. After mating, the female will lay her eggs just below the mouth of a new pitcher and the cycle begins anew. Amazingly, it has been found that the only other stimulus besides the urge to mate that can coax the moths to leave their pitchers is smoke. This is especially true for the southern species as the bogs in which they live are subject to frequent fires. If they were to remain in the pitchers, it is likely that entire populations would be incinerated.

As terrifying as this sounds for the moths, fire is essential to their lifecycle. The pitcher plant bogs of southeastern North America could not persist without fire. When fires are suppressed, these bogs inevitably fill in with more aggressive vegetation such as swamp titi (Cyrilla racemiflora) or any of the myriad invasive species that grow in this region. As bogs become choked with woody shrubs and trees, pitcher plants and other bog species are choked out to the point that they can completely disappear. Fire in these habitats brings more life than it does death.

A population of Sarracenia flava var. rubricorpora showing signs of a thriving Exyra moth population in the form of damaged and bent over pitchers.

Given that the pitchers of pitcher plants function as both photosynthetic organs and a means to obtain nutrients like nitrogen and phosphorus, it stands to reason that damage from pitcher plant moths could harm the plants over the long term. Indeed, high densities of pitcher plant moths can exact quite a toll on pitcher plant individuals. Evidence from multiple sites has shown that heavily damaged pitcher plants can shrink in size over time, indicating loss of energy reserves. In support of this, some have also found that highly damaged pitcher plants go on to produce more pitchers, which indicates that such individuals are prioritizing more nutrient capture. In ecosystems already defined by nutrient scarcity, the effects of herbivory on these carnivorous plants are likely more severe than they are for plants growing in nutrient-rich environments. However, it should be noted that it is a rare case in which pitcher plant moths exact such a toll on plants as to completely kill the pitcher plants they rely on for survival.

That being said, there is plenty of room for concern over the future of both pitcher plants and moths. Only 3% of the bogs that once existed in southeastern North America remain today. Habitat loss means fewer populations of plants and thus less habitat for the moths (and myriad other lifeforms) that rely on them. For these reasons and more, habitat protection and restoration must be made a high priority moving into the future. Please consider supporting a land conservation/restoration organization in your area!

![Sarracenia leucophylla flower. Photo by Noah Elhardt licensed by GNU Free Documentation License [SOURCE]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/544591e6e4b0135285aeb5b6/1567376504321-A9HVCAG8Y3DY9IMUJMGT/Sarracenia_leucophylla_flower.jpg)

![Sarracenia leucophylla habitat. Photo by Brad Adler licensed by CC BY-SA 2.5 [SOURCE]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/544591e6e4b0135285aeb5b6/1567376707208-INV6TWZMXE1UXVO4DAHQ/Sarracenia_leucophylla_field.jpg)

![[SOURCE]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/544591e6e4b0135285aeb5b6/1486578795815-PMLOXE5169FQ31BLAB9V/image-asset.jpeg)