Pereskia aculeata photo by scott.zona licensed under CC BY 2.0

At first glance, there is little about a Pereskia that would suggest a relation to what we know as cacti. Even a second, third, and forth glance probably wouldn't do much to persuade the casual observer that these plants have a place on cacti family tree. All preconceptions aside, Pereskia are in fact members of the family Cactaceae and quite interesting ones at that.

Most people readily recognize the leafless, spiny green stems of a cactus. Indeed, this would appear to be a unifying character of the family. Pereskia is proof that this is not the case. Though other cacti occasionally produce either tiny, vestigial leaves or stubby succulent leaves, Pereskia really break the mold by producing broad, flattened leaves with only a hint of succulence.

Pereskia spines are produced from areoles in typical cactus fashion. Photo by Frank Vincentz licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0

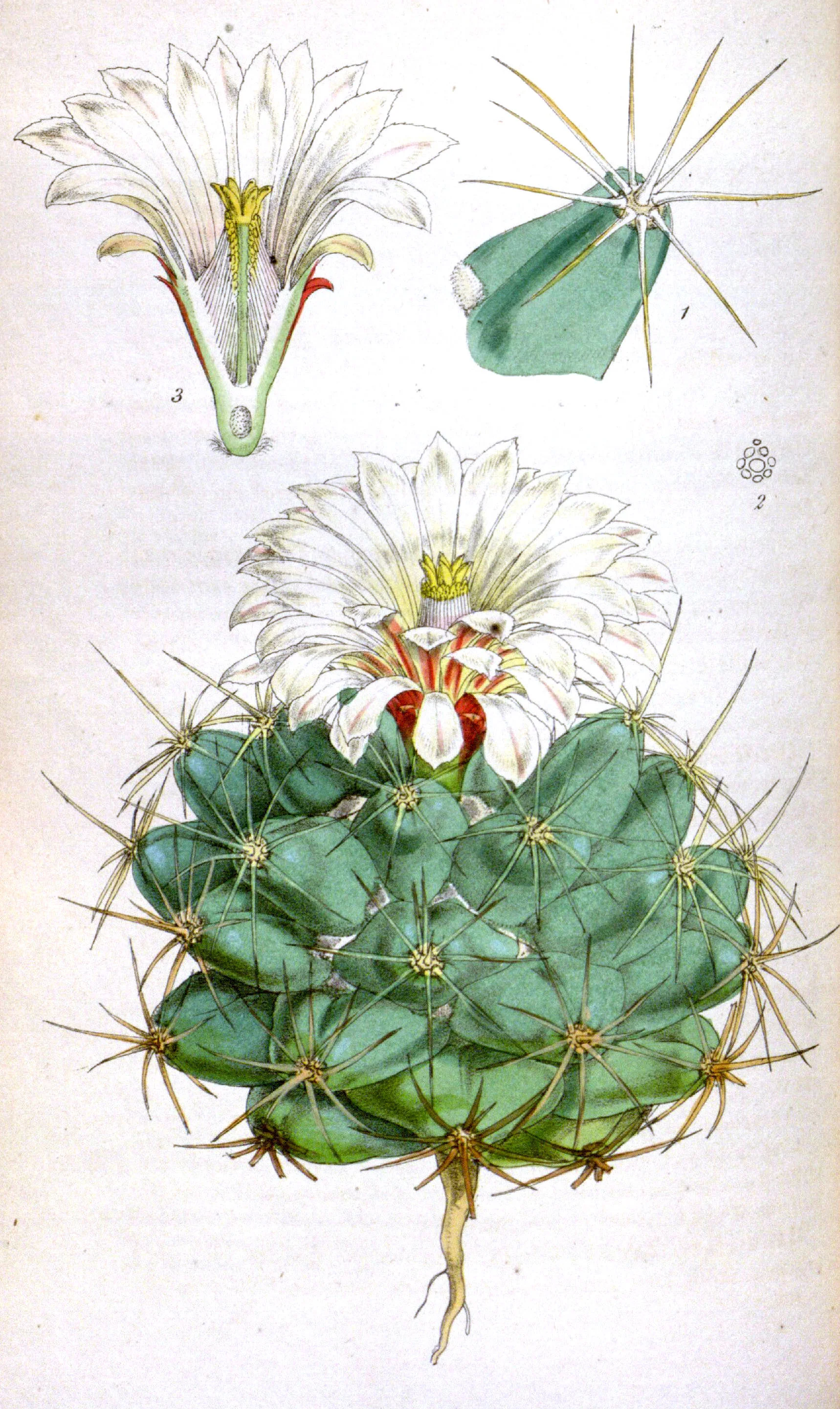

What's more, instead of clusters of Opuntia-like pads or large, columnar trunks, Pereskia are mainly shrubby plants with a handful of scrambling climbers mixed in. Similar to their more succulent cousins, the trunks of Pereskia are usually adorned with clusters of long spines for protection. Additionally, each species produces the large, showy, cup-like blooms we have come to expect from cacti.

They are certainly as odd as they are beautiful. As it stands right now, taxonomists recognize two clades of Pereskia - Clade A, which are native to a region comprising the Gulf of Mexico and Caribbean Sea (this group is currently listed under the name Leuenbergeria) and Clade B, which are native to regions just south of the Amazon Basin. This may seem superficial to most of us but the distinction between these groups has a lot to teach us about the evolution of what we know of as cacti.

Pereskia grandifolia Photo by Anne Valladares (public domain)

Genetically speaking, the genus Pereskia sorts out at the base of the cactus family tree. Pereskia are in fact sister to all other cacti. This is where the distinction between the two Pereskia clades gets interesting. Clade A appears to be the older of the two and all members of this group form bark early on in their development and their stems lack a feature present in all other cacti - stomata. Stomata are microscopic pours that allow the exchange of gases like CO2 and oxygen. Clabe B, on the other hand, delay bark formation until later in life and all of them produce stomata on their stems.

The reason this distinction is important is because all other cacti produce stomata on their stems as well. As such, their base at the bottom of the cactus tree not only shows us what the ancestral from of cactus must have looked like, it also paints a relatively detailed picture of the evolutionary trajectory of subsequent cacti lineages. It would appear that the ancestor of all cacti started out as leafy shrubs that lacked the ability to perform stem photosynthesis. Subsequent evolution saw a delay in bark formation, the presence of stomata on the stem, and the start of stem photosynthesis, which is a defining feature of all other cacti.

Pereskia aculeata Photo by Ricardosdag licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0

If you are as excited about Pereskia as I am, then you , my friend, are in luck. A handful of Pereskia species have found their way into the horticulture trade. With a little luck attention to detail, you too can share you home with one of these wonderful plants. Just be warned, they get tall and their spines, which are often hidden by the leaves, are a force to be reckoned with. Tread lightly with these wonderfully odd cacti. Celebrate their as the evolutionary wonders that they are!

Photo Credits: [1] [2] [3] [4]