Plants do not have immune systems like animals. Instead, they have evolved an entirely different way of dealing with infections. In trees, this process is known as the "compartmentalization of decay in trees" or "CODIT." CODIT is a fascinating process and many of us will recognize its physical manifestations.

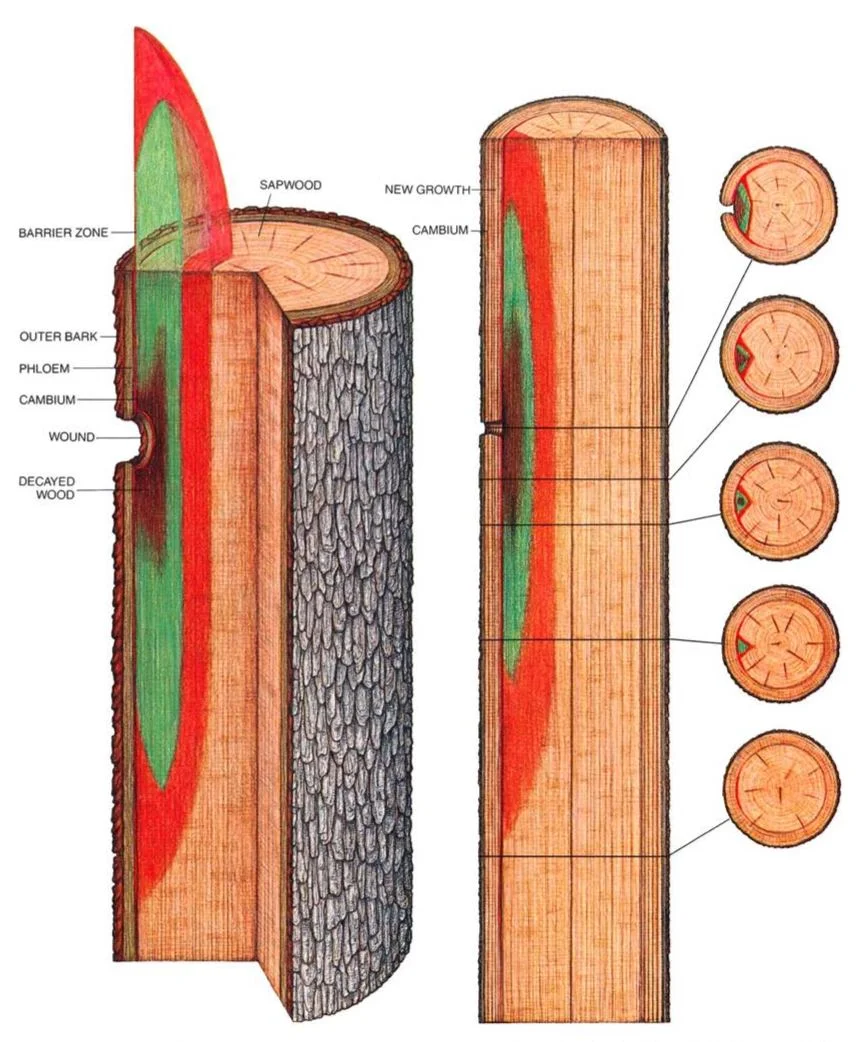

In order to understand CODIT, one must know a little something about how trees grow. Trees have an amazing ability to generate new cells. However, they do not have the ability to repair damage. Instead, trees respond to disease and injury by walling it off from their living tissues. This involves three distinct processes. The first of these has to do with minimizing the spread of damage. Trees accomplish this by strengthening the walls between cells. Essentially this begins the process of isolating whatever may be harming the living tissues.

This is done via chemical means. In the living sapwood, it is the result of changes in chemical environment within each cell. In heartwood, enzymatic changes work on the structure of the already deceased cells. Though the process is still poorly understood, these chemical changes are surprisingly similar to the process of tanning leather. Compounds like tannic and gallic acids are created, which protect tissues from further decay. They also result in a discoloration of the surrounding wood.

The second step in the CODIT process involves the construction of new walls around the damaged area. This is where the real compartmentalization process begins. The cambium layer changes the types of cells it produces around the area so that it blocks that compartment off from the surrounding vascular tissues. These new cells also exhibit highly altered metabolisms so that they begin to produce even more compounds that help resist and hopefully stave off the spread of whatever microbes may be causing the injury. Many of the defects we see in wood products are the result of these changes.

The third response the tree undergoes is to keep growing. New tissues grow around the infected compartment and, if the tree is healthy enough, will outpace further infection. You see, whether its bacteria, fungi, or a virus, microbes need living tissues to survive. By walling off the affected area and pumping it full of compounds that kill living tissues, the tree essentially cuts off the food supply to the disease-causing organism. Only if the tree is weakened will the infection outpace its ability to cope.

Of course, CODIT is not 100% effective. Many a tree falls victim to disease. If a tree is not killed outright, it can face years or even decades of repeated infection. This is why we see wounds on trees like perennial cankers. Even if the tree is able to successfully fight these repeat infections over a series of years, the buildup of scar tissues can effectively girdle the tree if they are severe enough.

CODIT is a well appreciated phenomenon. It has set the foundation for better tree management, especially as it relates to pruning. It is even helping us develop better controls against deadly invasive pathogens. Still, many of the underlying processes involved in this response are poorly understood. This is an area begging for deeper understanding.

Photo Credits: kaydubsthehikingscientist & Alex Shigo

Further Reading: [1]

![An example of the soda bottle terrariums. Photo by Kara Nelson [source]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/544591e6e4b0135285aeb5b6/1514928056661-E031RMQD8KDRVW6RCINO/image-asset.png)

![[SOURCE]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/544591e6e4b0135285aeb5b6/1512592058594-10U3VAD3XSE19TP8YE08/hydrocera.JPG)

![[SOURCE]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/544591e6e4b0135285aeb5b6/1512593517035-7TIRATWNLG5L5T1SA0GH/hydro+dist.JPG)

![Cockroach pollinating C. sellowiana. [SOURCE]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/544591e6e4b0135285aeb5b6/1511459932769-DPB6RO5OJ48IZVNPL6LH/roach+pollination.JPG)

![[SOURCE]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/544591e6e4b0135285aeb5b6/1510771591218-E7STZ1TS2LEW7CZUCQFX/nph14859-fig-0001.png)