There has been an uptick in conversations about plant-fungal interactions recently. News of trees communicating via a vast subterranean network of fungal threads has everyone looking at forests like one big commune. Though it feels nice to think of these relationships as altruistic, such simplified takes on the subject overlook the fact that plants and the mycorrhizal fungi they partner with have entered into a mutual exchange, allowing each player to gain from the interaction.

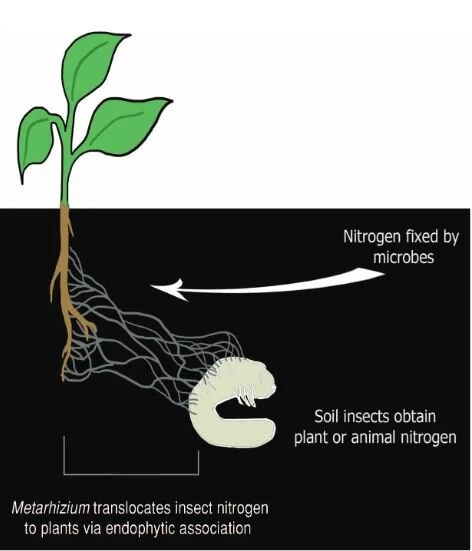

The reciprocity of these relationships are exquisitely illustrated in the partnering of fungi in the genus Metarhizium and their botanical hosts. Metarhizium are predominantly insect pathogens, invading the bodies of soil-dwelling insects, killing them, and absorbing nutrients like nitrogen that are locked up within their tissues. Though extremely good at obtaining compounds like nitrogen from insects, these fungi can not readily access the carbon they need to survive. That is where plants come in.

Plants are experts at producing carbon-based compounds. Via photosynthesis, they break apart CO2 molecules and turn them into carbon-rich sugars for food. However, they need nitrogen to do this. Unfortunately for plants, most of the nitrogen on our planet is locked up in forms they can’t readily access. It is likely that plants’ relative inefficiency at obtaining the nitrogen they need to survive is a major driving force for the partnering between plants and soil-dwelling fungi.

A beetle grub infected by a Metarhizium fungus. Photo by CSIRO (CC BY 3.0)

Over the last few years, scientists studying the relationship between Metarhizium and plants have discovered that a fascinating and ecologically important exchange has evolved among these organisms. When plants are presented with adequate nitrogen, many species will end up over-producing carbohydrates. Their fungal partners are the ones to benefit from this as those excess carbohydrates are fed to the fungi living on or in the plants’ roots. Indeed, via some complex experiments using isotopes of carbon and nitrogen, scientists were able to demonstrate that killing and eating insects isn’t the only way Metarhizium fungi make a living.

In addition to eating insects, Metarhizium also form mycorrhizal relationships with the roots of numerous plant species from grasses to beans. In doing so, they are able to obtain carbohydrates. However, the plants aren’t giving their photosynthates away for free. In exchange, the fungi are providing them with ample nitrogen that was obtained by infecting and digesting their insect prey. By tracing the path of carbon and nitrogen isotopes between fungi and plants, scientists found that the fungi were supplying the plants directly with insect-derived nitrogen.

This may not sound terribly surprising. After all, this is more or less how most mycorrhizal interactions work. However, the fact that an insect-killing fungus is transferring nitrogen from insect to plant directly, rather than from already decomposed materials in the soil reveals a rather novel pathway in the nitrogen cycle of our planet. Metarhizium is an extremely common and widespread genus of fungi and it is likely that these relationships are not unique to the plants used in these studies. The wide-spread nature of these relationships means that this way of cycling nitrogen and carbon through an ecosystem is also extremely common and wide spread.

It is important to remember that relationships like these are a benefit to plants and fungi alike (sorry insects). Both parties stand to gain from the mutualism. It isn’t that plants are plugging into this system and using it to help each other out. To me, it makes far more sense that fungi like Metarhizium benefit from keeping as many healthy plants in their network as possible. We can’t forget that like plants, fungi are organisms fighting to survive long enough to get their genes into the next generation. Mutualisms are not altruisms. They are mutual exchanges that benefit both parties.