Plants go to great lengths to attract pollinators. From brightly colored flowers to alluring scents and even some sexual deception, there seems to be no end to what plants will do for sex. Recently, research on the pollination of a species of cactus endemic to the Ecuadorian Andes suggests that even plant hairs can be co-opted for pollinator attraction.

Espostoa frutescens is a wonderful columnar cactus that grows from 1,600 ft (487 m) to 6,600 ft (2011 m) in the Ecuadorean Andes. Like many other high elevation cacti, this species is covered in a dense layer of hairy trichomes. These hairs serve an important function in these mountains by protecting the body of the plant from excessive heat, cold, wind, and UV radiation. Espostoa frutescens takes this a step further when it comes time to flower. It is one of those species that produces a dense layer of hairs around its floral buds called a cephalium. Cacti cephalia are thought to have evolved as a means of protecting developing flowers and fruits from the outside elements. What scientists have now discovered is that, at least for some cacti, the cephalium may also serve an important role in attracting bats.

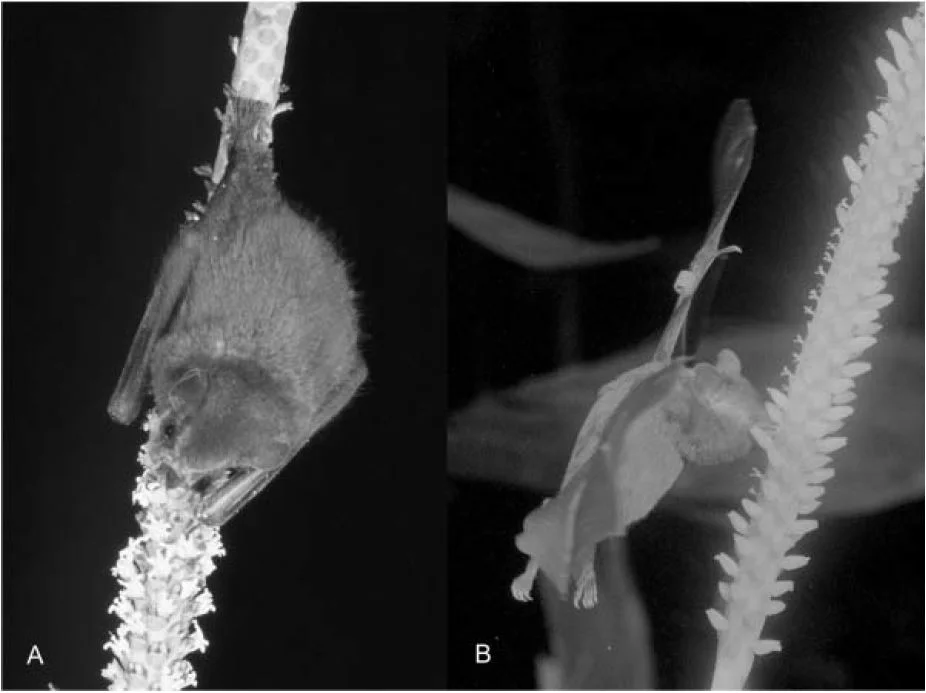

Bats are famous for their use of echolocation. Because they mainly fly at night, bats rely on sound and scent, rather than sight to find food. More and more we are realizing that a lot of plants have taken advantage of this by producing structures that reflect bat sonar in such a way that makes them more appealing to bats. Some plants, like Mucuna holtonii and Marcgravia evenia, do this for pollination. Others, like Nepenthes hemsleyana, do this to obtain a nitrogen-rich meal.

Espostoa frutescens apparently differs from these examples in that its not about reflecting bat sonar, but rather absorbing it at specific frequencies. Close examination of the hairs that comprise the E. frutescens cephalium revealed that they were extremely well adapted for absorbing ultrasonic frequencies in the 90 kHz range. This may seem arbitrary until you look at who exactly pollinates this cactus.

The main pollinator for E. frutescens is a species of bat known as Geoffroy’s tailless bat (Anoura geoffroyi). It turns out that Geoffroy’s tailless bat happens to echolocate at a frequencies right around that 90 kHz range. Whereas the rest of the body of the cactus reflects plenty of sound, bat calls reaching the cephalium of E. frutescens bounced back an average of 14 decibels quieter.

Essentially, the area of floral reward on this species of cactus presents a much quieter surface than the rest of the plant itself. It is very possible that this functions as a sort of calling card for Geoffroy’s tailless bats looking for their next meal. This makes sense from a communication standpoint in that it not only saves the bats valuable foraging time, it also increases the chances of cross pollination for the cactus. To obtain enough energy from flowers, bats must travel great distances. Anything that helps them locate a meal faster will increase visitation to that flower. By changing the way in which the flowers “appear” to echolocating bats, the cacti thus increase the amount of visitation from bats, which brings pollen in from cacti located over the bats feeding range.

It is important to note that, at this point in time, research has only been able to demonstrate that the hairs surrounding E. frutescens flowers are more absorbent to the ultrasonic frequencies used by Geoffroy’s tailless bat. We still have no idea whether bats are more likely to visit flowers borne from cephalia or not. Still, this research paves the way for even more experiments on how plants like E. frutescens may be “communicating” with pollinators like bats.

Further Reading: [1]

![[SOURCE]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/544591e6e4b0135285aeb5b6/1508201752975-7W5T194C1IK9IC4ZE62M/batpass1.JPG)

![[SOURCE]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/544591e6e4b0135285aeb5b6/1508203341477-I655ZRIK84ZNM78XLMYE/image-asset.jpeg)