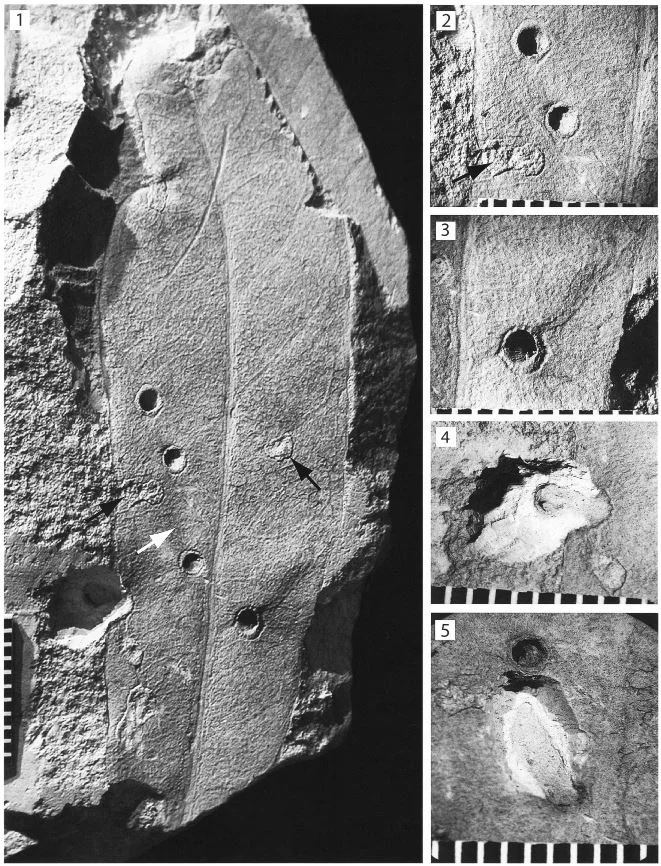

Leucospermum arenarium in the field and one of its pollinators, Gerbillurus paeba, feeding on flowers. (A) Pollen presenter contact on G. paeba. (B) G. paeba foraging on L. arenarium [Source]

It may come as a surprise to some that small mammals such as rodents, shrews, and even marsupials have been coopted by plants for pollination services. Far from being occasional evolutionary oddities, many plants have coopted small furry critters for their reproductive needs. Some of the best illustrations of this phenomenon occur in the Protea family (Proteaceae).

Protea nana. Photo by SAplants licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0

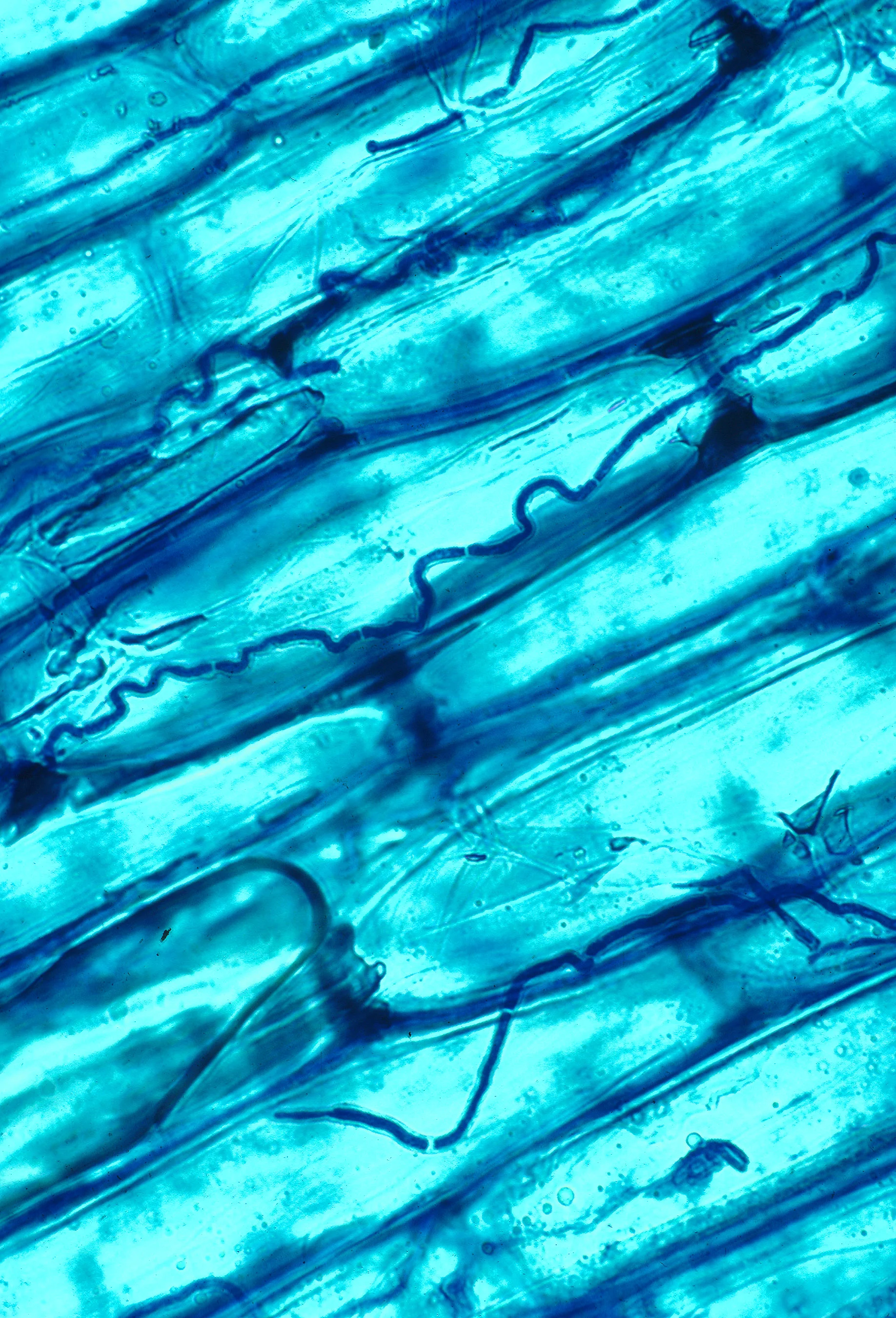

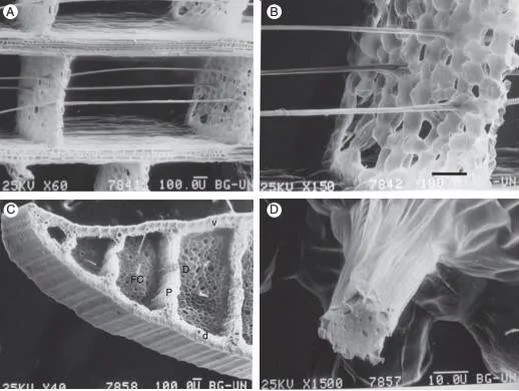

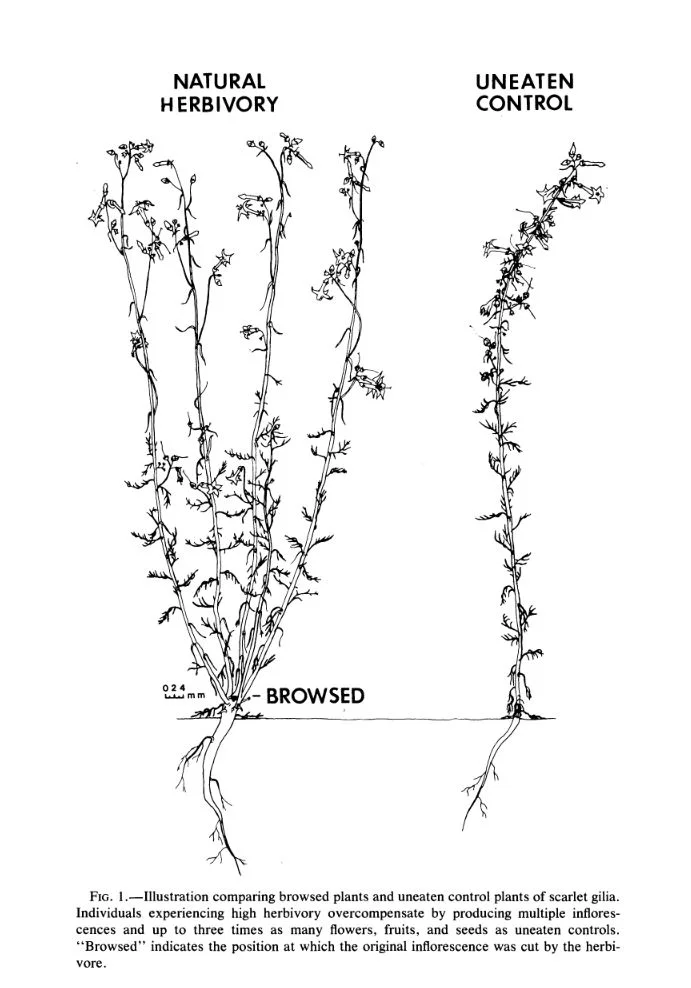

The various members of Proteaceae are probably best known for their bizarre floral displays. Indeed, they are most often encountered outside of their native habitats as outlandish additions to the cut flower industry. Superficial interest in beauty aside, the floral structure of the various protea genera and species is complex to say the least. They are well adapted to ensure cross pollination regardless of what the inflorescence attracts. Most notable is the fact that pollen doesn’t stay on the anthers. Instead, it is deposited on the tip of a highly modified style, which is referred to as the pollen presenter. Usually these structures remain closed until some visiting animal triggers their release.

The inconspicuous floral display of Protea cordata. Photo by SAplants licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0

Although birds and insects have taken up a majority of the pollination needs of this family, small mammals have entered into the equation on multiple occasions. Pollination by rodents, shrews, and marsupials is collectively referred to as therophilly and it appears to be quite a successful strategy at that. Therophilous pollination has arisen in more than one genera within Proteaceae.

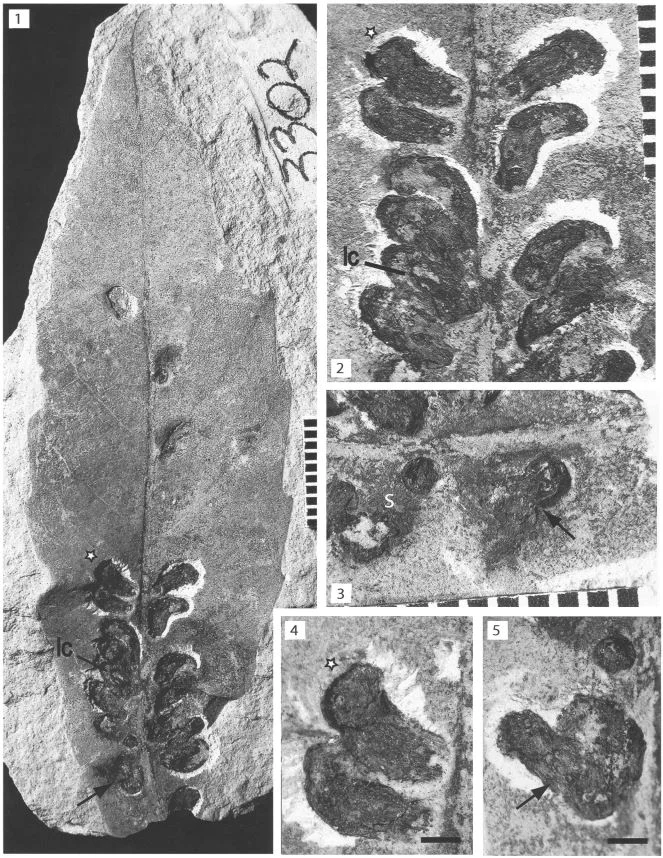

A therophilous pollination syndrome appears to come complete with a host of unique morphological characters aimed at keeping valuable pollen and nectar away from birds and insects. The inflorescences of therophilous species like Protea nana, P. cordata, and Leucospermum arenarium are usually tucked deep inside the branches of these bushes, often at or near ground level. They are also quite robust and sturdy in nature, which is thought to be an adaptation to avoid damage incurred by the teeth of hungry mammals. The inflorescences of therophilous proteas also tend to have brightly colored or even shiny flowers surrounded by inconspicuous brown involucral bracts.

(C) Flowering L. arenarium with dense, mat-forming inflorescences. (D) Geoflorous inflorescences. (E) Pendulous inflorescences above ground level. [Source]

Contrasted against bird pollinated proteas, these inflorescences can seem rather drab but that is because small mammals like rodents and shrews are drawn in by another sense - smell. Therophilous proteas tend to produce inflorescences with strong musty or yeasty odors. They also produce copious amounts of sugar-rich, syrupy nectar. Small mammals, after all, need to take in a lot of calories throughout their waking hours and it appears that proteas use that to their advantage.

A small mouse pollinating Protea nana

As a rodent or shrew slinks in to take a drink, its head gets completely covered in pollen. In fact, they become so dusted with pollen that, before small, easy to hide trail cameras became affordable, pollen loads in the feces of rodents were the main clue that these plants were attracting something other than birds or insects. What’s more, the flowering period of many of these therophilous proteas occurs in the spring, right around the time when many small mammals go into breeding mode. Its during this time that small mammals need all of the energy they can get.

As odd as it may seem, rodent pollination appears to be a successful strategy for a considerable amount of protea species. The proteas aren’t alone either. Other plants appear to have evolved therophilous pollination as well. Nature, after all, works with what it has available and small mammals like rodents make up a considerable portion of regional faunas. With that in mind, it is no wonder that more plants have not converged on a similar strategy. Likely many have, we just need to take the time to sit down and observe.

![Leucospermum arenarium in the field and one of its pollinators, Gerbillurus paeba, feeding on flowers. (A) Pollen presenter contact on G. paeba. (B) G. paeba foraging on L. arenarium [Source]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/544591e6e4b0135285aeb5b6/1537827836454-8MRDJYZTEWG0C9Z67RLJ/pro2.PNG)

![(C) Flowering L. arenarium with dense, mat-forming inflorescences. (D) Geoflorous inflorescences. (E) Pendulous inflorescences above ground level. [Source]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/544591e6e4b0135285aeb5b6/1537827887634-OUACGBZFIHJR2VX4TIL9/pro3.PNG)

![Saintpaulia intermedia [source]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/544591e6e4b0135285aeb5b6/1534796840068-JU8QYYE0NL5913H8O2C2/saintpaulia+intermedia.jpg)

![[source]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/544591e6e4b0135285aeb5b6/1533585937843-ART57F0111IK2ZJH43ZX/late+fall.JPG)