Photo by Wendy Cutler licensed by CC BY-SA 2.0

Succulent passionflowers?! It took me a minute to get my head wrapped around the idea. It wasn’t until I saw one in flower that I truly understood. The genus Adenia is found throughout east and west Africa, Southeast Asia, and hits its peak diversity in Madagascar. It comprises approximately 100 species and, as a whole, is poorly understood. Today I would like to introduce you to this bizarre genus within Passifloraceae.

Adenia glauca Photo by Karelj licensed under the GNU Free Documentation License

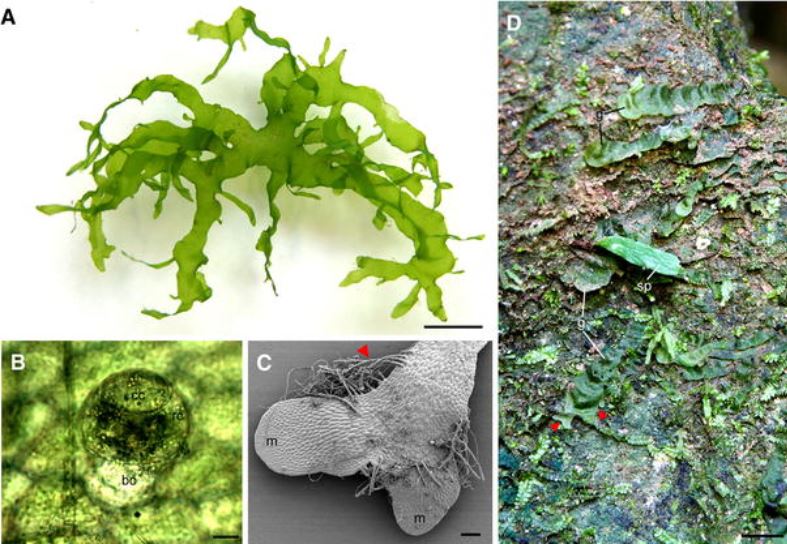

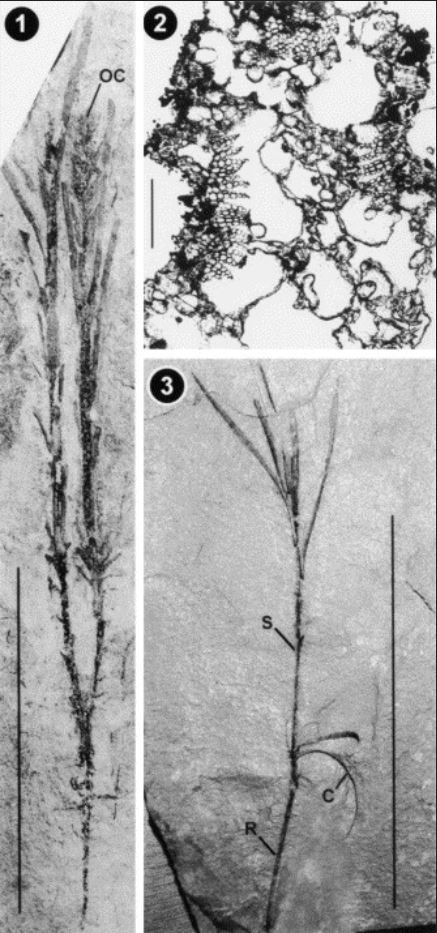

Adenia is, to date, the second largest genus within the Passionflower family and yet delineating species has been something of a nightmare for botanists over the years. At least some of this confusion lies within the diversity of this odd group. It has been said that few angiosperm lineages surpass Adenia in the diversity of growth forms they exhibit. Though all could be considered succulent to some degree, Adenia runs the gamut from trees to vines, and even tuberous herbs.

Even within individual species, the overall form of these plants can vary widely depending on the conditions under which they have been growing. Their succulent nature and that fact that many species can reach rather large proportions means that herbarium records for this group are scant at best. Many are only known from a single, incomplete collection of a few bits and pieces of plant. Also, juvenile plants often look very different from their adult forms, making timing of the collection crucial for proper analysis.

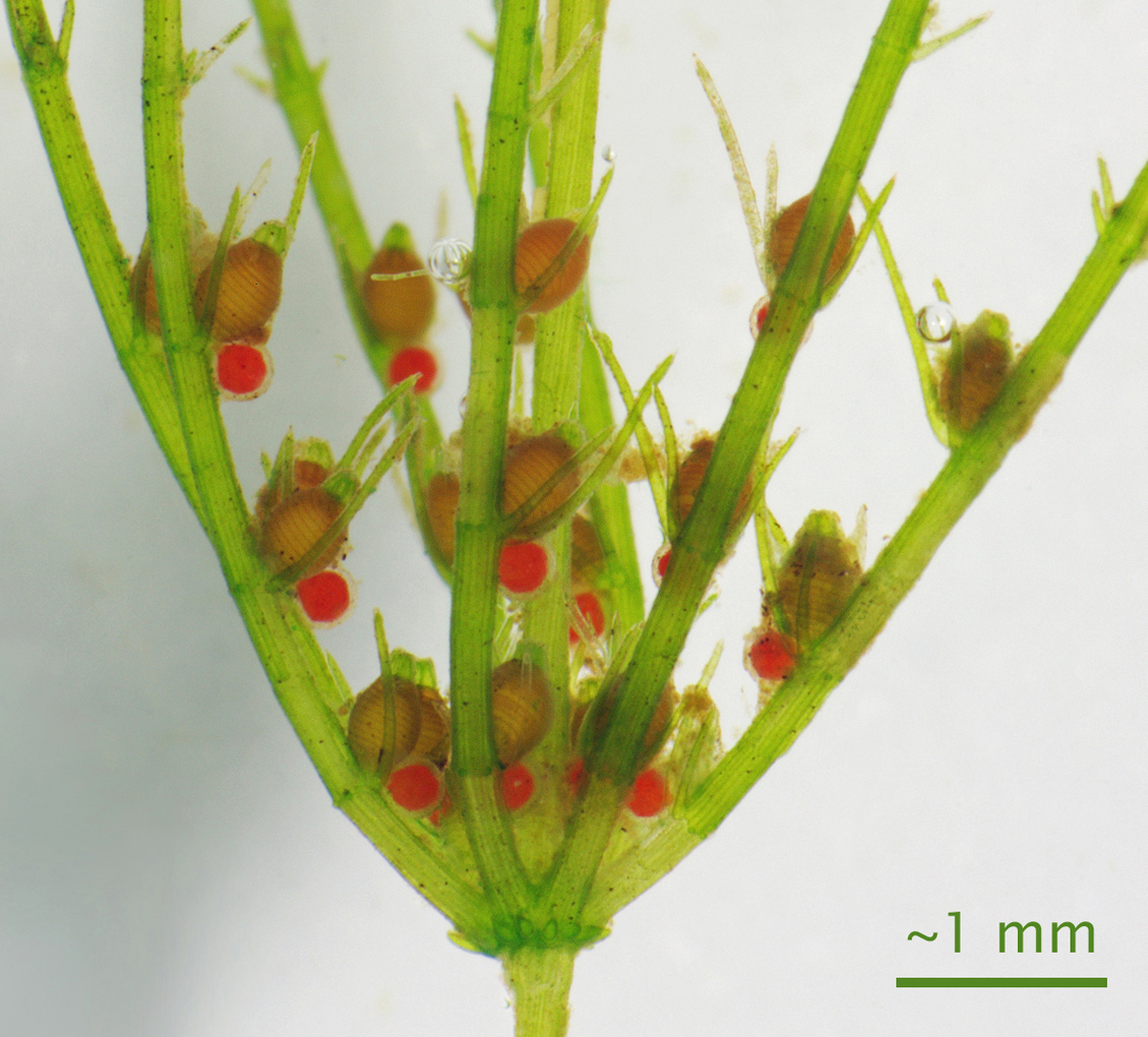

To complicate matters more, all Adenia are dioecious, meaning that individual plants are either male or female. Male and female flowers of individual species look pretty distinct and differ a bit from what we have come to expect out of the passionflower family. Often collections were made on only a single sex. This is further complicated by the fact that these plants often exhibit very short flowering seasons. Most come into bloom right before the onset of the rainy season and are entirely leafless at that point in time. Because of this, it has been extremely difficult to accurately match flowering collections to vegetative collections. As such, nearly 1/4 of all Adenia species are missing descriptions of either male or female flowers and their fruits.

Female flower of Adenia reticulata. Photo by C. E. Timothy Paine licensed under CC BY-NC 2.0

Male flowers of Adenia digitata. Photo by Joachim Beyenbach licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0

Flowers of Adenia firingalavensis. Photo by voyage-madagascar.org licensed under CC BY 2.0

Fruits of Adenia hondala

Even genetic work has failed to clear up much of the mysteries that surround this group. Some studies suggest that Adenia is sister to all other genera within Passifloraceae whereas others have even suggested it to be nestled neatly within the genus Passiflora. The most recent work hints at a placement among the tribe Passifloreae. If this confuses you, you are certainly not alone. Until a more complete sampling effort is done on Adenia, I think it is safe to say that this genus will be holding onto its taxonomic mysteries for the foreseeable future.

Adenia globosa photo by KENPEI licensed under the GNU Free Documentation License

All Adenia are perennial plants but how they manage this differs from species to species. Some put all of their energy into underground tubers, producing annual stems and leaves that die back each year. Others don’t produce any tubers and instead store all of their water and nutrients within thick stems. This has made at least a handful of species a hit with succulent growers around the world. It is always an interesting sight to see a giant caudiciform trunk or base with bunches of spindly stems spraying out from the top.

Leaves and fruit of Adenia cissampeloides. Photo by International Institute of Tropical Agriculture licensed under CC BY-NC 2.0

Juvenile Adenia glauca. Photo by laurent houmeau licensed under CC BY-SA 2.0

Adenia are also extremely toxic plants. The conditions under which these plants evolved are tough and it appears that this group doesn’t want to take any chances on losing any biomass to herbivores. The main class of compounds they produce are called lectins. These proteins cause myriad issues within animal bodies including rapid cell death, blood clotting, inhibition of protein synthesis, and a disruption of ribosome and DNA function. Needless to say, its in any critters best interest to avoid nibbling on any species of Adenia. Even handling and pruning of these plants merits caution.

Photo by Wendy Cutler licensed under CC BY 2.0

Whether you’re a botanist, taxonomist, gardener, or just curious about plant diversity, Adenia is a wonderful example of just how many unknowns are still out there. Regardless of their taxonomic status, these are fascinating species, each with a wonderful ecology and intriguing evolutionary history. These plants are hardy survivors and a great example of the lengths a genus can go to when presented with new opportunities. Undoubtedly many more species await description but the plants we currently know of are fascinating to say the least.

Adenia pechuelii. Photo by Ewald Schmidt licensed under public domain.

![Photo by Edwino S. Fernando [source]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/544591e6e4b0135285aeb5b6/1550353497346-FB5R33TTIU4UMX2RE0X7/Rafflesia_consueloae_open_flower.jpg)