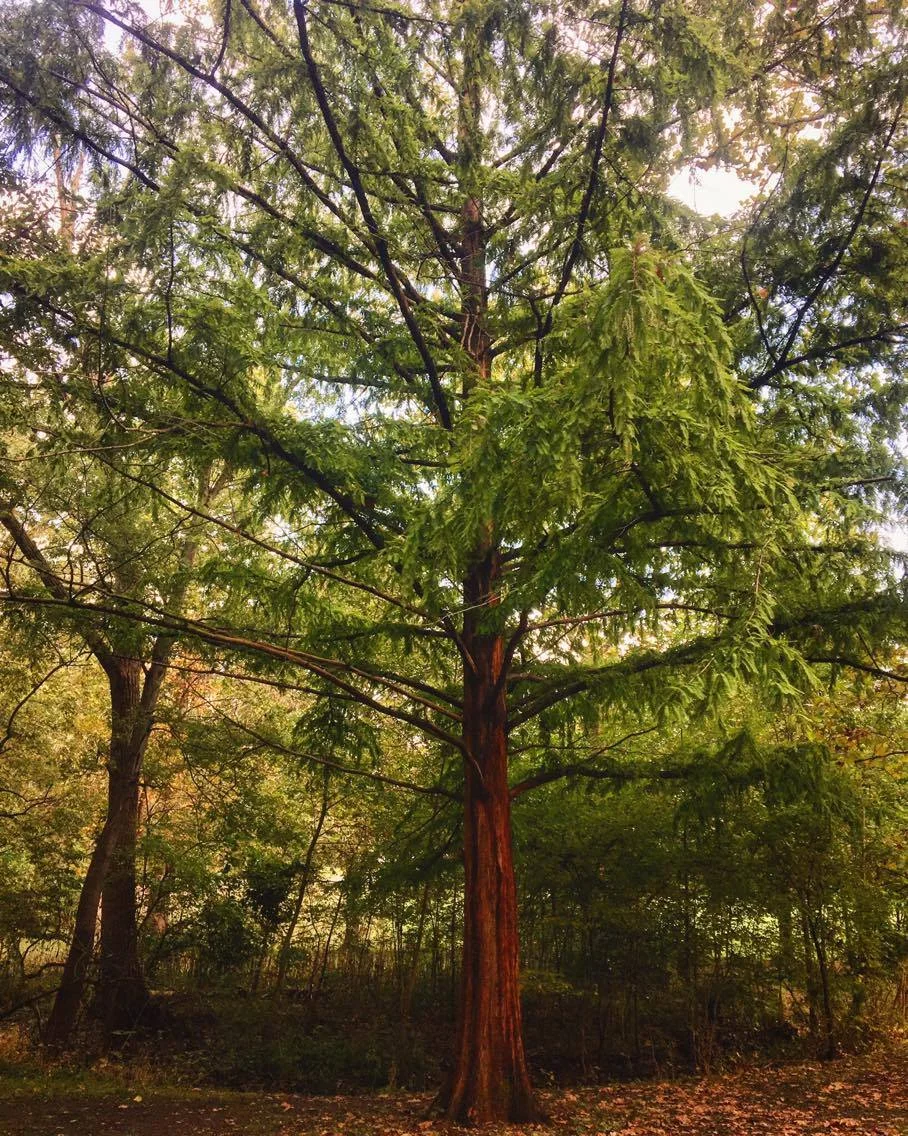

Photo Credit: Howard Falcon-Lang, Royal Holloway University of London

What you are looking at here is the oldest fossil evidence of the genus Pinus. Now, conifers have been around a long time. I mean really long. Recognizable members of this group first came onto the scene sometime during the late Triassic, some 235 million years ago. Today, one of the most species-rich genera of conifers are those in the genus Pinus. They dominate northern hemisphere forests and can be found growing in dry soils throughout the globe. For such a commonly encountered group, their origins have remained a bit of a mystery.

The fossil was discovered in Nova Scotia, Canada. Unlike the rocky fossils we normally think of, this fossil was preserved as charcoal, undoubtedly thanks to a forest fire. The degree of preservation in this charcoal specimen is astounding and provides ample opportunity for close investigation.

I mentioned that this fossil is old. Indeed it is. It dates back roughly 133 –140 million years, which places it in the lower Cretaceous. What is remarkable is that it predates the previous record holder by something like 11 million years. Even more remarkable, however, is what this tiny fossil can tell us about the ecology of Pinus at that time.

Firstly, the leaf scars indicate that this tree had two needles per fascicle. This implies that the genus Pinus had already undergone quite the adaptive radiation by this time. If this is the case, it pushes back the clock on pine evolution even earlier. Another interesting feature are the presence of resin ducts. In extant species, these ducts secrete highly flammable terpenes, which would have potentially promoted fire.

Species that exhibit this morphology today often utilize an ecology that promotes devastating crown fires that clear the land of competition for their seedlings. Although more evidence is needed to confirm this, it nonetheless suggests that such fire adaptations in pines were already shaping the landscape of the Cretaceous period. All in all, this fossil is a reminder that big things often come in small packages.

Photo Credit: Howard Falcon-Lang, Royal Holloway University of London

Further Reading:

![A liverwort “trap” showing the lid (L), water sac (wl). {SOURCE]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/544591e6e4b0135285aeb5b6/1453484005585-XO0ZD7MMGIVHXPW0JU5M/image-asset.jpeg)

![[SOURCE]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/544591e6e4b0135285aeb5b6/1453483994540-FO0ROSLCBG9A6TRN9HHJ/image-asset.jpeg)