I love the ocotillo (Fouquieria splendens) for many reasons. It is an impossible plant to miss with its spindly, spine-covered stems. It is a lovely plant that is right at home in the arid parts of southwestern North America. Beyond its unique appearance, the ocotillo is a fascinating and important component of the ecology of this region.

My first impression of ocotillo was interesting. I could not figure out where this plant belonged on the tree of life. As a temperate northeasterner, one can forgive my taxonomic ignorance of this group. The family from which it hails, Fouquieriaceae, is restricted to southwestern North America. It contains one genus (Fouquieria) and about 11 species, all of which are rather spiky in appearance.

Of course, those spines serve as protection. Resources like water are in short supply in desert ecosystems so these plants ensure that it is a real struggle for any animal looking to take a bite to get at the sap inside. Those spines are tough as well. One manged to pierce the underside of my boot during a hike and I was lucky that it just barely grazed the underside of my foot. Needless to say, the ocotillo is a plant worthy of attention and respect.

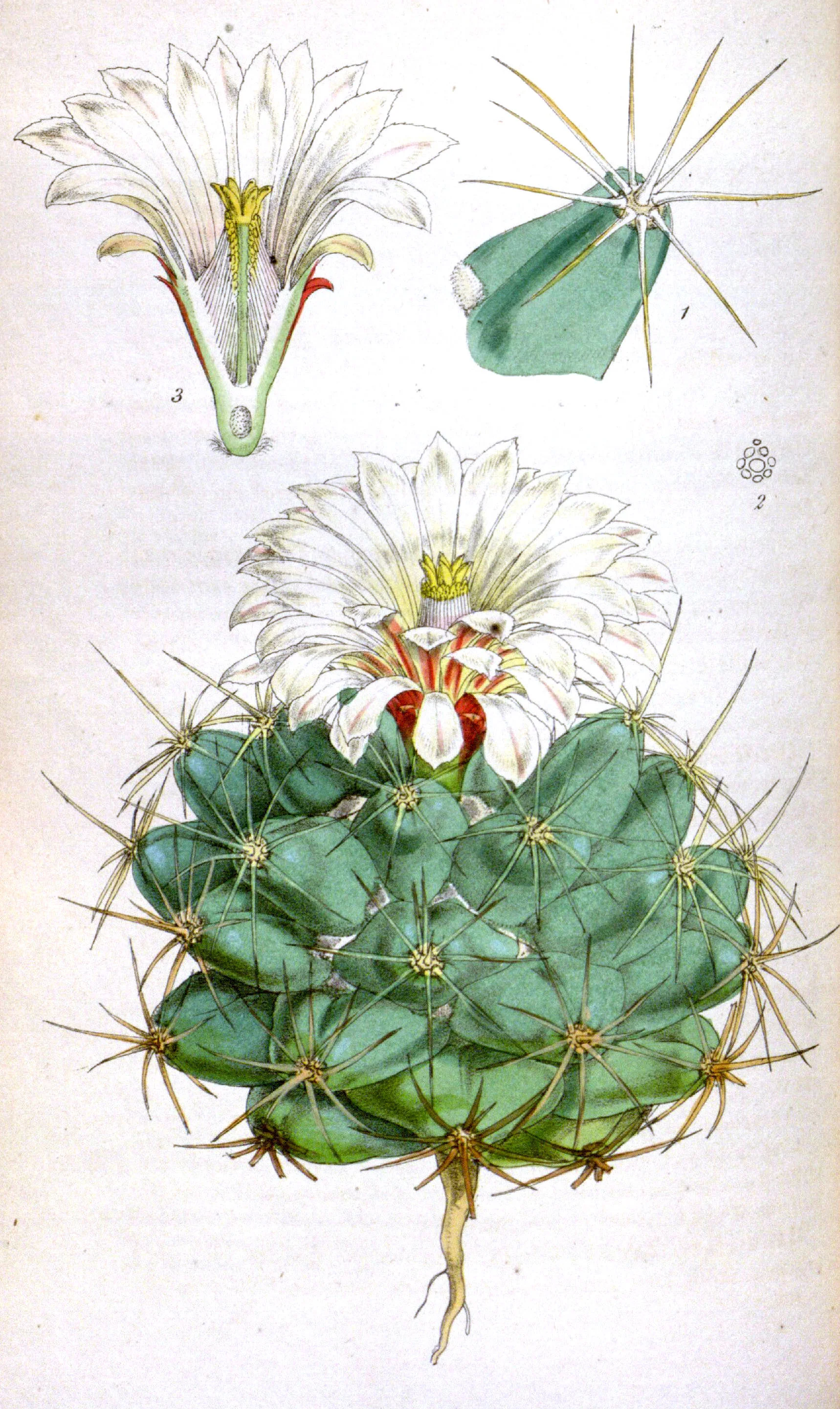

One of the most striking aspects of ocotillo life is how quickly these plants respond to water. As spring brings rain to this region of North America, ocotillo respond with wonderful sprays of bright red flowers situated atop their spindly stems. These blooms are usually timed so as to take advantage of migrating hummingbirds and emerging bees. The collective display of a landscape full of blooming ocotillo is jaw-droppingly gorgeous and a sight one doesn't soon forget. It is as if the whole landscape has suddenly caught on fire. Indeed, the word "ocotillo" is Spanish for "little torch."

Flowering isn't the only way this species responds to the sudden availability of water. A soaking rain will also bring about an eruption of leaves, turning its barren, white stems bright green. The leaves themselves are small and rather fragile. They do not have the tough, succulent texture of what one would expect out of a desert specialist. That is because they don't have to ride out the hard times. Instead, ocotillo are what we call a drought deciduous species, producing leaves when times are good and water is in high supply, and dropping them as soon as the soil dries out.

This cycle of growing and dropping leaves can and does happen multiple times per year. It is not uncommon to see ocotillo leaf out up to 4 or 5 times between spring and fall. During the rest of the year, ocotillo relies on chlorophyll in its stems for its photosynthetic needs. Interestingly enough, this poses a bit of a challenge when it comes to getting enough CO2. Whereas leaves are covered in tiny pours called stomata which help to regulate gas exchange, the stems of an ocotillo are a lot less porous, making it a challenge to get gases in and out. This is where the efficient metabolism of this plant comes in handy.

All plants undergo respiration like you and me. The carbohydrates made during photosynthesis are broken down to fuel the plant and in doing so, CO2 is produced. Amazingly, the ocotillo (as well as many other plants that undergo stem photosynthesis) are able to recycle the CO2 generated by cellular respiration back into photosynthesis within the stem. In this way, the ocotillo is fully capable of photosynthesis even without leaves.

Through the good times and the bad, the ocotillo and its relatives are important components of desert ecology. They are as hardy as they are beautiful and getting to see them in person has been a remarkable experience. They ad a flare of surreality to the landscape that must be seen in person to believe.

![Stems climbing on fallen dead wood (a) or on standing living trees (b). A thick and densely branched root clump (c) and thin and elongate roots (d) [Source]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/544591e6e4b0135285aeb5b6/1518471929195-C99KP24U24J238YMX055/myco+roots.JPG)

![Mentzelia phylogeny showing reduction in seed wings. [source]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/544591e6e4b0135285aeb5b6/1517881654366-84BORS8KUYHRY6IUK9DQ/ajb21811-fig-0002.png)